The date is September 24, the 104th minute of the match, and Javí Martínez has just gotten the better of Sevilla’s goalkeeper, Jasín Bunú, ensuring Bayern Munich’s victory in the UEFA Super Cup. The final was watched by over fifteen thousand wild fans. Budapest’s Ferenc Puskás Stadium was UEFA’s testing ground for the return of fans into the stands after the spring pandemic, with the naive belief that the virus had been defeated forever. Puskás Aréna, opened in 2019, is one of the newest and most modern European stadiums and it cost Hungarian taxpayers some 567 million euros. Viktor Orbán clearly decided that rather than enter uncertain waters, it would be better to stick to the tried and tested authoritarian approach of “bread and circuses” – support of football infrastructure is among his key investments. The announced renovation and construction of several dozen other stadiums (the first of which, as coincidence would have it, in Orbán’s home village) could cost up to 598 million euros, some sources claim.

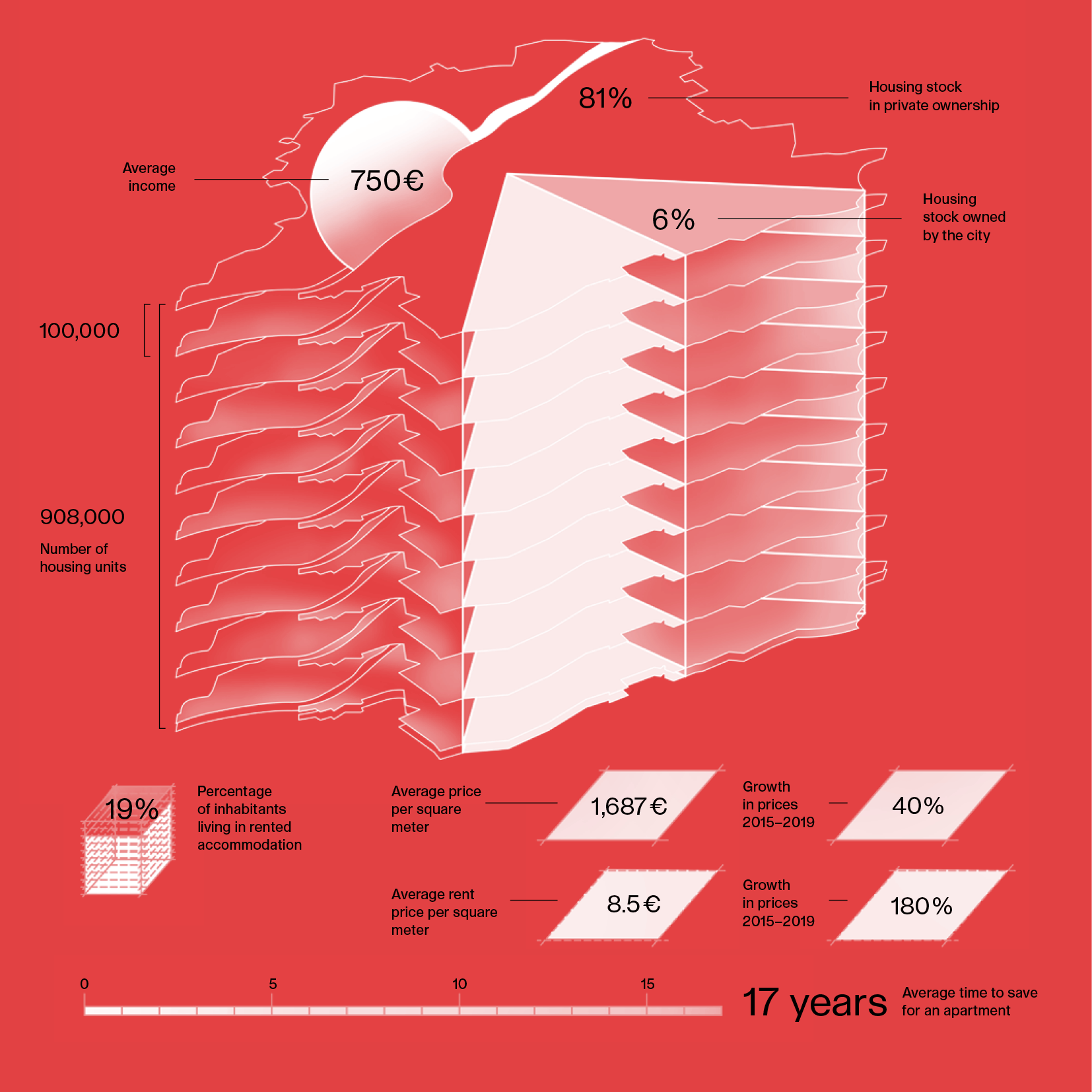

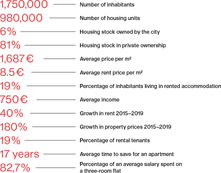

While the construction of one of Budapest’s new landmarks swallowed up vast sums, the city around it is falling into an increasingly pressing housing crisis, which is, in some respects, the worst in the European Union. Rents have more than doubled over the course of the last ten years and property prices have grown by up to a hundred and eighty per cent in some districts.

In lucrative locations, a square metre goes for as much as four thousand euros. In Hungary, over thirty per cent of all households spend over half their income on housing, and in Budapest, the number is even higher.[1] According to Eurostat, quoted by the Hungarian National Bank in its report on the housing market, the Hungarian capital is the fourth worst in unaffordable housing in the EU – after Paris, Prague, and Bratislava.[2] Hungary also regularly leads European tables regarding the number of people living in inadequate conditions. Though the situation has improved considerably over the last few years, Hungary is still fifth, following Romania, Latvia, Bulgaria, and Poland. Orbán’s government might claim the quality of housing in the country is improving, but many experts agree that the nation’s leadership is doing practically nothing to make housing more affordable and ameliorate the housing crisis.

The liberal dream

“In practice, all those statistics mean that for a young person, like me, it’s practically impossible to rent an apartment, or worse yet, buy one,” says Csaba Jelinek, an urban sociologist and anthropologist from the Péfiferia research centre, in a pub a stone’s throw away from the Puskás stadium.[3] “It depends on the district, but the centre is virtually unavailable for someone from the lower middle class.” According to Jelinek, this is the result of years of neglect of public housing policy. “Since the revolution, no government has proposed any truly progressive housing policies. The dominant discourse is the classic denial of state intervention based on historical experiences from before 1989. The state should not intervene in housing, after all, it did not act like a prudent businessman and mismanaged public property,” explains Jelinek.

Before 1989, almost 50 per cent of Budapest’s apartments were owned by the city, but tenants also had certain proprietary rights. “As a tenant, I could exchange my apartment for another, or even change rental housing for ownership. The price at which these exchanges took place were around 50 per cent of the market price,” says the sociologist and economist József Hegedüs from the Metropolitan Research Institute (MIT). “It was essentially a grey economy transferred into official waters. According to our research, some 30 per cent of people in the 1980s acquired housing in this manner.”

As early as the 1980s, Hungary became relatively liberal in the context of the Eastern Bloc – among other things, the privatisation of housing began before the fall of the regime. Fifty thousand apartments were privatised before 1989 and the process continued after the revolution. Hungarian privatisation, or rather restitution, was different from the Czech case in that it was not possible to receive an entire house (with tenants included), but only individual housing units. The previous owners could apply for compensation, but this wasn’t very high.

As a result of these factors, the rental housing sector in Hungary is highly non-transparent and unregulated. “We have virtually no data – we don’t know who’s renting what to whom and for how much, it usually takes place on an unofficial basis,” says Hegedüs as he tries to explain the local system. This leads to a great uncertainty on both sides, but particularly for tenants, who can lose their accommodation very easily. “But I’ve also heard of many cases in which the tenant did not pay rent and the landlord had to pay him to leave the apartment,” continues the sociologist. “This disorganised situation is convenient for many people and interest groups. But our institute proposes at least partial regulation,” he adds.

Thirty years after the revolution, the city’s housing stock represents only about 6 per cent of all the apartments in Budapest. Just like in other post-communist cities, the city therefore has limited options for supporting affordable housing and protecting its inhabitants from the negative impacts of financialisation and gentrification.

Municipal property continued to be sold off in recent years, even as property and rent prices skyrocketed. According to the 2019 Annual Report on the Housing Crisis in Hungary, in 2017, another 536 apartments in Budapest were privatised.[4]

Housing benefit. Decent families with children only, please

After the year 2000, as the economy grew, mortgages in foreign currencies (usually in euros and Swiss francs) with floating interest rates became very popular among Hungarians. The cheaper they were, however, the riskier. This was confirmed in 2008, when a mortgage crisis broke out, closely followed by a global economic crisis. Hungary was one of the most severely affected states – the state debt was over 70 per cent of the GDP and Hungarian households owed over six billion euros. Two years later, the economic and political crisis gave rise to Viktor Orbán as the country’s leader.

“That was perhaps the first time housing became a topic of discussion across society – the crisis affected hundreds of thousands of people across all classes, including the richest,” explains Csaba Jelinek. “It took years before we got out of the crisis, but it didn’t give rise to any public support for housing. Or at least not in a form that would truly help the social groups most in need,” he remarks. Though the government created a programme to increase the birth rate and support economic growth, within which it offers families with children subsidies and loans for housing, in order to be eligible for these funds, you must conform to a number of criteria, including a certain income level and a clean criminal record. “This support therefore doesn’t make its way to the poor families at risk, but is mostly reserved for the financially secure middle classes,” says Jelinek. The system therefore ultimately aids the increasing differences between various social groups.

In Budapest, the governmental programme had a further negative impact – some 40 per cent of all families that received the housing benefit did not use the money to acquire housing in the metropolis, instead opting for a house in one of the urban agglomerations surrounding Budapest. This strengthened the generally criticised trend of suburbanisation. The government itself admitted a partial failure, especially after the programme and the dire situation became the point of critique from the Hungarian National Bank, as the extreme rise in housing prices began endangering the entire financial market.

We (don’t) want foreigners in Hungary

“Unaffordable housing has always been an issue for the poor. But today, it is also an issue for the middle classes, including the well-educated younger generations,” says Áron Horváth, an economist at ELTINGY, the Centre for Property Research at Eötvös Loránd University. “Most of our students spend some time at universities abroad. They would then like to return, but more and more often, I hear that when they compare the costs of living, moving back here simply isn’t worth it,” explains Horváth. “Housing prices are lower in Dutch or British cities (except London), and they often have the opportunity to get better work for better money there.”

Everyone agrees that without the help of their families, young people simply cannot find housing here.

Insufficient availability of municipal rental apartments, the unregulated private sector, unsystematic state support, and also the slim offer of affordable private housing, along with the typically Eastern European desire for home ownership at any cost all contribute to the fact that over 40 per cent of Hungarians between the ages of 25 and 34 live with their parents. And all these factors continue driving prices up.

In Budapest, there is the added element of the attractiveness of the centre for Hungarian and international investors and the large number of apartments used for short-term tourist rentals. On top of that, property is increasingly being acquired as an investment. “Housing has become a commodity. The upper middle class and the wealthy are now investing much more in housing than in the stock market. And again, that contributes to the creation of social inequality, which has grown considerably in past decades,” says József Hegedüs. It is not only the local elites who are storing their money in property – there are foreign investors too, and this despite the fact that Hungary’s leadership continues to claim that it is restricting the influence of foreigners and foreign powers in the country.

Orbán’s regime influences (not only) the housing policy of the city to a much greater extent than is commonly found in the state–capital city relationship elsewhere in Europe. Though we could describe the official discourse as neoliberal dogma, Orbán’s government is also strengthening the position of the state, which some experts interpret as the sign of a centralist system.

But Csaba Jelinek describes the current Hungarian system as merely another form of neoliberalism, linked to elements of authoritarianism and economic nationalism. “As for housing policy, the central position is still that the state should not interfere too much; that it is not the role of the state to build houses,” explains Jelinek. Even the family subsidies mentioned above aren’t provided by the state directly – banks are used as intermediaries. “What we had before was classic neoliberalism: we have to privatize, even though the ones privatising and investing were generally foreigners. Then Orbán introduced the idea that they had to be replaced by Hungarians, so he gave the local oligarchs much greater power.”

But most development projects, especially in the centre of Budapest, involve investors from abroad. Jelinek claims that we can assume many of them are profiting from good political relationships. Áron Horváth speaks of the old government programme, The Hungarian Investor Residency Bond Program, in which foreign nationals could receive Hungarian citizenship in return for an investment over a certain sum. The programme was mostly popular with the Chinese and citizens from the Middle East. “I don’t think it was a completely transparent programme. Hundreds of apartments were sold to foreign investors this way,” claims Horváth. Though this programme has been terminated, it was replaced by another, focused directly on the property market: the Hungarian Real Estate Residency Program. “The residency permit will be based on the profit of your real estate investment. The simplest way to acquire it is to purchase at least two apartments in Budapest and rent them out with the aim of generating profit,” we read on the website of the New Residency company, which organises the programme. All you need to get a residency permit for you and your family is an investment of at least two hundred thousand euros in “one of the most dynamically developing real estate markets in the European Union.”[5]

Head to head

Wandering around Budapest, you don’t exactly feel like you’re in a real estate dream. The tattered buildings are beautiful and they possess a romantic charm, but I doubt their tenants feel just as charmed. Solutions to the sorry state of the housing stock and making housing more available are some of the priorities of the new leadership of the city. The opposition won the autumn 2019 municipal elections, Gergely Karácsony from the Dialogue party became mayor, and the opposition also formed governing coalitions in many city districts. The ruling party’s failure in local elections, however, meant it fortified its centralising tendencies, further limiting the cities’ autonomy. The government is primarily trying to limit budgets. This year’s pandemic was a welcome pretext that allowed the government to confiscate large sums from cities’ budgets as part of extensive extraordinary measures. The eighth and ninth district, for instance, where the housing crisis in Budapest is at its worst, lost hundreds of millions of forints intended for the renovation of municipal apartments and aid for poor families, as reported by Balkan Insight.

Although the city hall now has at its disposal a proposal for the city’s housing policy from 2020 to 2030 developed by MIT, Bálint Misetics, an expert on social policy and housing and an advisor to Budapest’s city hall, points out that it is unclear how much of the proposal will be carried through and enforced. The core of the institute’s plan lies in broadening the segment of available rental housing in three basic ways: through better and more effective care for the current housing stock, by establishing a non-profit agency to administer the municipal housing stock and expand it, and through support of alternative forms of ownership (condominiums, cooperatives, and others). If the city were to follow this strategy, the proportion of municipal or agency housing would rise to 12 per cent, up to 30 per cent in the long-term. At this stage, however, all these are just proposals on paper.

Where do the poor go?

After the coronavirus outbreak, most tourists disappeared from Budapest, so thousands of apartments used for short-term rentals returned to the market and rental costs decreased slightly. Regulating tourist rentals was one of the central tenets of Karácsony’s programme, to which end the mayor met with Airbnb representatives shortly after last year’s election. “That was more a diplomatic meeting to clarify our respective positions – we didn’t have a legislative tool to limit this type of rentals,” explains Misetics.

August 2020, however, saw the ratification of an amendment of a trade law that gives local politicians the right to restrict short-term rentals, most directly regarding the number of days for which apartments can be rented this way. In Budapest, however, this decision is not up to the city hall but to individual city districts. “Airbnb is lobbying against the new regulations and we’re trying to get the municipalities to cooperate and unify the rules as much as possible,” says Misetics. “In any case, apartments should only be rented for short-term rentals for a smaller part of the year from now on.”

Airbnb and other platforms often state that only about ten to fifteen thousand apartments in Budapest are used for short-term rentals, i.e. about 1 per cent, so tourist rentals have no impact on the cost and availability of housing. “This is a highly misleading statement. Budapest is a large city, and of its twenty-three districts, only about seven are affected by this phenomenon,” says Misetics. “In the central districts, it might well be more than half of all apartments, perhaps even three quarters.”

Especially in the centre, recent years have seen the progression of gentrification processes that have been hardest on the city’s poorest inhabitants. The central areas on the Pest side (where the parliament is) are now lucrative and popular with tourists. Traditionally, however, the central districts of Budapest were working class, poor, with a high percentage of Roma population, and highly socially stigmatised. The relocation of the original inhabitants has been taking place since 1989, but it gathered speed particularly in the past decade. “Thanks to the fact that only individual apartments could be restituted and privatised, a highly specific mosaic-like ownership structure was created here, and it didn’t allow investors to buy entire houses or blocks,” explains Csaba Jelinek. “In this respect, we’re lucky compared to Prague, because this prevented the quick displacement of the inhabitants and the transformation of the centre into a Disney Land park. But investors find a way, of course.”

A right to dignity

Following a recommendation from journalist Eszter Neuberger, who focuses on social issues and housing, I visit Hös Utca, the location of one of Budapest’s famous socially excluded districts, stigmatised by the mainstream media as a hub for a variety of negative social phenomena. In reality, it is home to dozens of families, mostly Roma, who have the “good fortune” – for now – to live in these houses (though they are falling apart), and not in tents in the park or beyond the city borders. According to public opinion, a walk through Hös Utca would likely be dangerous for my health, but I wouldn’t really have noticed I was walking through a “problem district” if I hadn’t been alerted to this fact in advance. The only sign of social exclusion is the sorry state of the houses, but that is nothing uncommon in Budapest. Poverty strikes the eye even harder in a city where hundreds of millions of euros are being invested in giant development projects.

The surroundings of Puskás Ferenc Stadion underground station, where I board my train back to the centre, are full of homeless people and others clearly from the poorest strata of society. This tableau is typical of all the metropolises of the world, but I meet many more poor and begging people in Budapest than in, say, Prague, and not just at the central transport nodes. According to József Hegedüsz, some 15 per cent of Hungarians can be described as very poor, but another 70 per cent represents classes in precarious circumstances, with no security they won’t lose their job or apartment, leading to serious problems.

I give the rest of my cash to an older gentleman playing the guitar on the dirty tiles in an underpass. He looks like he might have been teaching high school English just last week. Perhaps he still has a job, but it’s no longer enough to live off. I have nothing left for the pensioner sitting at the other exit, so I avert my eyes. After a few days in Budapest, one can hardly avoid thinking about the banal but crucial fact that here, poverty is robbing people of one of the most valuable things they have – their dignity.

English translation: Ian Mikyska