Vienna is different: this is an advertising slogan of a city which embraces uniqueness. The message reveals its ultimate aptness when we tackle the theme of death. Some people believe that in this respect the whole city is a unique open-air museum of sorts. Poets go so far as to contend that an “authentic” Viennese should arrive to this world already as a museum object; and if we trust literature and music, he should also be attributed with a very peculiar attitude towards death and dying.

An inevitable question follows, who is responsible for this: is it the Viennese themselves (we should define “Viennese” first, as since the Austro-Hungarian empire they constituted an assorted multicultural mix), or is it the city of Vienna itself that should answer for this particular mind-set relating to death?

Nowhere else will you find the concept of a “beautiful funeral”, which has long oscillated between myth, stereotype, and reality. And yet how could it be otherwise, in the city, which boasts the municipal funeral service of Bestattung Wien, and the first ever museum devoted to the cult of the dead and the culture of burial? The museum offers a journey in time, within the sphere of the aesthetics of all matters terminal, which brings the taboo theme closer to the visitors. The range of museum objects is broad: from key testimonies of the phenomenon, via imperial treasures, to rarities of interest to connoisseurs.

The one and only anywhere in the world

The origins and circumstances surrounding the phenomenon go back to the days when the municipality took over private companies: in 1907, during the administration of Karl Lueger, the “Vienna city municipal corporation for the burial of the dead” was established. Three years later Lueger was already dead and buried in “a beautiful funeral” of his own, courtesy of the newly established enterprise. Within several decades, private funeral parlours were to be taken over, bought lock stock and barrel, which later became the foundation of the museum: this is a collection of objects bearing historical value, and originally intended for internal training purposes, so unique that they should not be kept from the public eye. In 1967, the first rocket was launched: the museum of funeral culture and cult of the dead in Vienna was inaugurated. Twenty years later, in this initially modestly endowed establishment, a wholly new concept of the museum arose: to arrange a display with a historically neutral design, based on the principle of creative dialogue between the exhibited objects and their viewers.

An event is way to go

The “beautiful funeral” purposefully winds through all the museum halls like a red thread, inviting a broad range of visitors to follow and participate: there are tourists, schoolchildren, university students, professionals, followers of alternative gothic and voyeurs… They all come thither to take part in this unique cultural-and-social event offered to them by the city of Vienna. After all, the “beautiful funeral” signifies worldly, elegant and glamorous funeral celebrations, which the new-fangled, wealthy bourgeois class brought to life in the last decades of the 19th century, and which the funeral industry managed to turn into an event of theatrical nature.

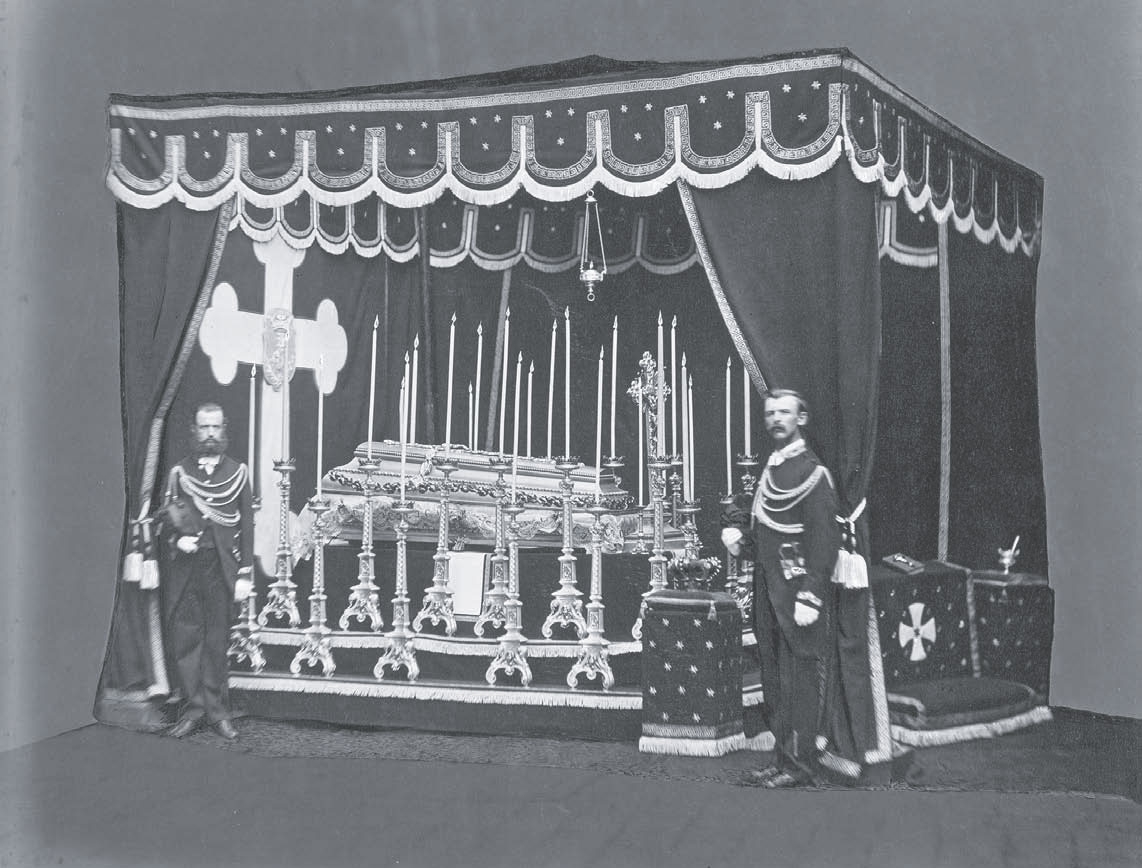

Following the magnificent funerals of aristocrats in the baroque era, the epoch of excess and exaggerated embellishment, the financially superior social classes performed their last self-presentation, resulting in the perfect staging of the dead body’s last passage, with additional features of a social event. It is not surprising that many a Viennese took a day off work and seized the opportunity of witnessing such an event.

The “Entreprise des Pompes Funèbres”, the first private funeral establishment which made such funerals possible, gave rise to a word in the Viennese dialect, “Pompfüneberer”, denoting the symbolical figure in a heavily decorated uniform, with the characteristic “ravioli” hat. The passage of the funeral procession, making its progress from the house throughout the city, was to be construed in the categories of drama: it was a kind of meticulously detailed theatre play, often following the courtly ceremony of Spanish aristocrats, and presented in a the pages of catalogues, which folded out fan-like, and offered the full range of order categories: from the “luxury full service” to the “economical funeral” model. It was however the funerals of the monarchs that inspired the greatest sensation of all.

The nostalgic royal-imperial grandeur of empress Zita

Whoever had proper apartments at their disposal, made sure to advertise the large size of the windows: you could hire them rather like theatre boxes, affording a better view of the spectacle. In addition, everyone was able to rent, at a deposit, a decent set of mourning clothes in one of the exclusive “funerary articles stores.”

The last time you might have experienced all that in Vienna was in the year 1989, on the occasion of the death of Zita, the last empress of Austria. Her funeral was quite a logistical challenge and a great event attended by international media from the world over: day-long celebrations, farewell by the people and the aristocracy, thousands of inscriptions in the book of condolences and a colourful ocean of wreaths. Places in appropriate windows were sold at exorbitant rates, the tourist industry reacted properly. Featuring in the republican menu for the wake celebrating Zita, countess of the Houses of Bourbons and Parma, was Parma ham with melon, of course. Besides, on the occasion of the funeral, pictures with the likeness of the deceased, postcards, and commemorative T-shirts were offered. On the first day of April at half past four in the afternoon, the “hour zero” arrived: after the celebrated requiem in the imperial cathedral, the funerary procession entered the city: the staging of joy within suffering had begun, the pompe funèbre for the “people as the guest of honour”, just like Zita had wished. She embarked on her ultimate journey in an illustrious, historical horse-drawn carriage, which had once served emperor Joseph I himself. The coachman’s uniform came from the museum’s deposit, of course. The coffin in the carriage was accompanied towards the crypt of Capuchins by Tyrolean guards in their bright-red feathered caps; the coach was preceded by regiments of nearly one thousand gunmen and militia with “monarchist” flags and badges, which afforded the conduct an astonishingly multi-colourful appearance. The traditional “tripartite division” of the Hapsburgs was somewhat moderated: the heart of Her Imperial Majesty already rests in the new crypt of the Muri Abbey in Switzerland, while the rest of her earthly remains here, in Vienna.

Falco’s ultimate rock-show

Fifty years living, nine years dead in his grave, today more alive than ever: Falco – an international rock star – is a truly Viennese phenomenon. Music lovers and rock fans in their younger days, the “MC Outsider Austria” motorcycle club members with their shaven heads, bushy beards, headbands, jeans and leather, came to lead him away. He himself was carried in a mahogany coffin, covered with a red ermine cloak à la King Louis II: the same cloak in which he happily paraded in one of his video clips. The music industry invited all the fans to the last event: Out of the dark, into the light.

Today, Falco’s grave is adorned with perhaps the most unusual monument of all times: a transparent, glass CD three meters in diameter, featuring the maestro himself, in a costume resembling a fusion between Batman and an angel. The fans leave their letters and presents there. His final place of rest in the Viennese Central Cemetery has served as a pilgrimage destination for years. As Mister Helmut Qualtinger, prototype author of Viennese popular literature, rightly noted, in Vienna you have to die first for people to drink toast to your health – but then, in turn, you will live very long. Public figures, especially those connected with culture and the stage, now still perceive their own funeral as the last, and sometimes the greatest, show. Falco with his cult following achieved true mastery in the field.

A dwelling for eternity

In Vienna, coffins were always in season; this kind of wooden pyjamas seemed universal enough and well suited for prolonged slumber. Ethnology recognises coffins as important vehicles used to travel to the afterlife; in the Occidental world they meet the guidelines ensuring the most efficient decomposition process possible, but sometimes they can also be perceived as a piece of furniture in the crypt-lodging, which should meet the needs of the buyer pertinent to his social status. Luxury models offer interiors with adjusted lighting and sumptuous casket decorations; while the key to the coffin – placed in a velvet-clad treasure chest – allows for a safe closure.

An emblematic image of those lamenting by the grave, and an urn with a broken column beneath the hanging branches of a weeping willow became two chief motifs that we shall find in metal-plated cardboard embellishments, leaves in the poetic albums of embossed coffin decorations. Companies of peculiar expertise issued thick sample catalogues with pictorial patterns alternating between “still art” and “already kitsch.” The freedom of choice was left as to certain parameters, such as for instance words “Rest in peace!”, or “May you sleep peacefully!”. You could have ordered the “Farewell!” in black, in gold, in silver, or with copper patina. In this manner the very cheapest of coffins were turned into proper imposing chests, thus making an impression of a beautiful, expensive funeral available also to those in the lower social strata.

The deceased members of the “Archduke’s House of Austria” were allotted to the overbearing tin sarcophagi in the private burial home of the Hapsburgs, the crypt of Capuchins, adorned with crowned skulls, royal emblems, or complete homage scenes from their past lives, in the full bloom of baroque splendour.

Joseph II, the elder brother of Maria Theresa, wished it altogether different, and had himself buried in a simple copper coffin to reflect the very essence of his Enlightenment concept of funerary reforms. Joseph attempted to put stop to bombastic luxury of funerals by means of royal decrees; traditions got the better of his plans in the end, while the very attempts of ending the attractive affectations of burials, even within the imperial family, shocked the town at large. He introduced the type of tombs structured like shafts, housing up to six persons one atop another. Even famous persons were buried in this manner, for instance Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was laid to rest in the Biedermeier style Cemetery of St. Marx.

In his contested royal decree of 1784 the enlightened emperor also directed that the so-called “Josephine” municipal coffin be introduces: it had a fitted mechanism to open the bottom part, so that the bodies thrown into it, sewn inside linen bags, would fall out below. Sprinkling lime upon them was to speed up the process of decomposition and allow for a faster relocation of graves, which was attractive from the perspective of saving space. You could close the coffin and use it again for the next set of corpses, at no additional cost. The rage of protests from the scandalised populace followed promptly. Less than a year later the emperor had to reconcile with the limitations to his power. The decree had to be called off, and the wealthy got their “beautiful funerals” back again.

The weirdest innovations were tried for the transportation of coffins: in addition to funerary streetcars and the funerary luxury train carriage of the Railroad Society (by means of which the body of the murdered empress Elisabeth was carried from Geneva to Vienna), the concept of “pneumatic” body transportation was conceived. It was to be a kind of large-scale pneumatic post, serving to dispatch coffins from downtown Vienna to the Central Cemetery, using the expedient of pressure. The project was rejected as not sufficiently pious.

Cremation and urns were in much lower demand in the city of Vienna. The containers seemed too small and insignificant to play a part in the theatre of the “beautiful funeral”, moreover, the “problem of metamorphosis” presented itself: particularly elderly people found it difficult to identify the loved one (a person of – say – 180 centimetres in height), when he was placed in such a small can. How infinitely easier it was to remember the departed, imagining him in a life-sized coffin… and that is why coffins in Vienna have always been regarded as indispensable elements of the eternal dwelling.

Two hundred years of hysteria around apparent death

The terrifying vision of being buried alive is probably one of the most primal fears perturbing man’s consciousness. As it became widespread throughout the 19th-century Europe, it caused a mass hysteria, the symptoms of which could be observed in all social strata. The overrated theme of apparent death became sensational in popular press.

Recent discoveries of academic medicine at the time, interested above all in exact determination of the cause and time of death, led to the establishment of morgues, which ensured the adequate waiting time for the burial. Subliminal fear however remained, even to this day; and we are reminded of it by the movies such as the one based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe, entitled Buried Alive, in which a small ray of hope, that the hour of parting might be postponed a little further, leads the protagonists to apply the most unusual rescue methods. Numerous inventors concocted a broad selection of appliances, ranging in scale from truly useful, via hilariously quaint, to inexplicably and roguishly utopian.

One famous instance in this field was the Viennese rescue alarm introduced in the local cemetery at Währing. The dead, who had to lie for 24 hours at the morgue just in case, had a string attached to their arm, connected to an alarm clock in the grave-digger’s home; a slightest movement would set off the alarm. In 1874, after the Viennese Central Cemetery was inaugurated, the device was improved using electromagnetic technology and made available to several dead persons at a time: a slightest movement was additionally signalled with a lit number. Thence it was a mere step to elaborate rescue-system coffins.

Next to these costly and sophisticated appliances, simpler solutions were also applied. Already during your life you could demand in your will that your heart should be pierced by the doctors after they had issued the death certificate. The association with vampire movie genre is a proper one, as the procedures were much alike: a double-edged dagger, 19 centimetres long, would pierce the heart, thus leaving not even a shadow of doubt as to the vivacity of the deceased. The long list of persons, who demanded to have their heart pierced, features many a noteworthy person, such as the writer and medic by education, Artur Schnitzler.

The life-like dead

Albin Mutterer, the pioneer of novel and ingenious photography, extended his offering thanks to a genius idea: his slogan – “We reproduce the deceased life-like, with striking similarity” – filled a market niche ideally. The concept of depicting the dead for one last time, in an appropriate lighting, led to the establishment of the first “atelier for corpses”; in 1854 the famous portrait of Dr. Petrus was conceived – so pleasant and faithful.

What was really striking, was above all the skilful recovery of a natural posture of the deceased, already stiff with rigor mortis, by seating them upon the chairs. When retouch artists drew the life-like eyes, the dead really came back to life, for one last time. Only the transportation of the dead to the atelier was a nuisance. It was done – unbelievable though it may seem – by public transport: they were placed alongside the living in a horse-drawn cab and carried across Vienna to the photographer. Not until two years later (in 1891) the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued a ban on this practice, on the grounds of public hygiene.

New museum on the rise

Since 2004, the Museum of Burial constitutes an independent institutional complex within the Vienna City Funeral Services. As far as private funerals are concerned, it plays a unique role of representing an institution responsible for the continuity of cultural heritage.

The concept of “edutainment”, an apt marriage of education and entertainment, developed specially for the needs of the exhibition which, by now, encompasses nearly 1000 museum objects, refers to the process of learning through an interactive tour of the museum with a curator. Museum lessons are heavily promoted, and tailor-made programs are offered to universities and specialised institutions, notably to the practitioners of palliative medicine.

Apart from the exhibition, the museum houses an archive of numerous texts and images with a substantial collection of parte (death notices), a special interest library of over three thousand volumes, document conservation and restoration studio, and a shop, in which you can purchase a piece of the museum and take it home as a memento.

Bestattung Wien goes art

In 2001, an incredible arts project was conceived: “a sitting coffin” – an homage to the surrealist painter René Magritte. Looking for new forms of expression, and intending to do away with a certain epoch in art history, which he considered passé, the pioneer of a new trend in art painted his own version of a canvas by his neo-classicist colleague Jean Jacques David, introducing a rectangular coffin into it. The idea was picked up anew on the occasion of “De Vota” funeral fair, held every three years: Magritte’s painting was copied out in three dimensions as an art installation, and reconstructed in a funeral parlour coffin.

The ever increasing public interest, the impact in the press and other media, as well as some initiatives by the Museum of Burial made the institution a kind of a turntable, a revolving target, where ever-influential past, the current present, and the already-begun future meet.

“With us you shall eternally rest in the right place.” This funeral parlour slogan may sound rather daring, yet it hits the spot, if placed within the context of the contemporary culture of event. Annual participation in the Night of the Museums was a great success and it placed the Museum of Burial among Vienna’s most unique. The event of the year 2008 was a special offer to test a coffin and lie in the box for a while – for those most brave among the visitors. More than 1200 people took part – and rested, for the first time ever, in the “Moira” casket…

Translated from Polish by Dorota Wąsik