Continuity and meaning in architecture and art

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.1

***

An interest in the significance of tradition is today usually seen as nostalgia and conservatism, and traditions should be left to the historians and anthropologists rather than discussed among artists and architects. In our age, obsessed with the notion of progress, the eyes are exclusively fixated on the present and the future. During the past few decades, uniqueness, invention and newness have become the sole criteria for quality in architecture, design and art. The coherence and harmony of the landscape or cityscape and their rich historical layring are not seen as objectives in architecture today. Artistic uniqueness and formal invention have, in fact, replaced the quest for existential meaning and emotive impact, not to speak of the desire for spiritual dimensions and beauty.

In his acceptance speech of the 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize in Beijing, the Chinese Laureate Wang Shu confessed that he had begun his career with works in the then fashionable Postmodern and Deconstructionist idioms, but he had eventually realized that his country was losing its connection with its own traditions and cultural identities. After this realization he has devotedly endeavored to tie his architecture to the long and deep cultural traditions of his country.2 This was an unexpectedly outspoken message in the presence of the highest Chinese officials. I believe that it was Wang Shu’s passionate message that has recently made the Chinese President Xi Jinping to express strong views against “imported” architecture and his support of Chinese traditions.

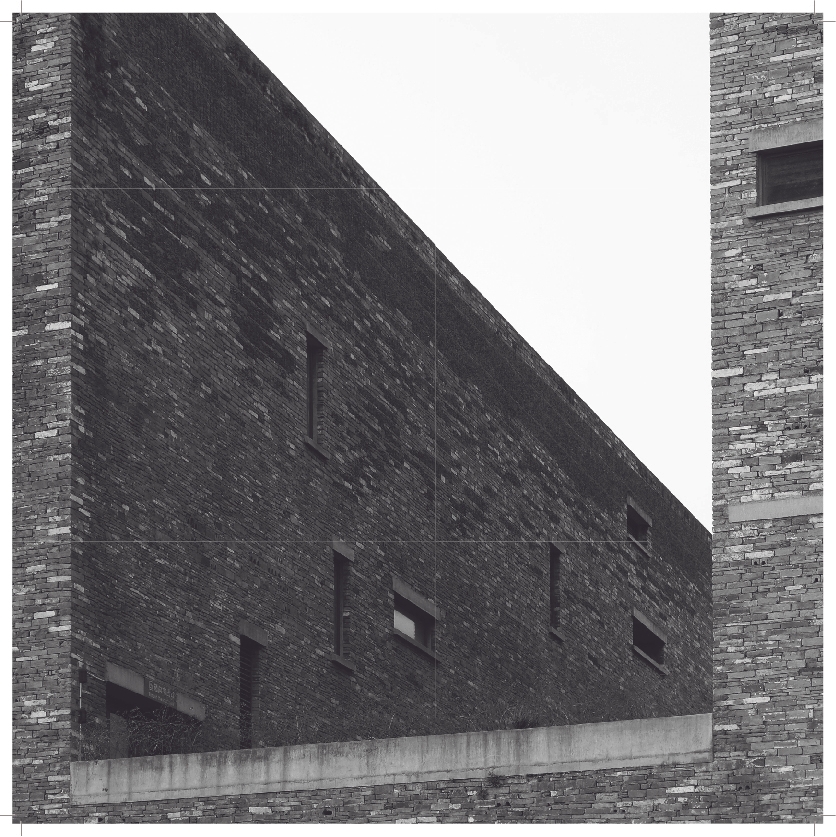

In his recent work Wang Shu has, indeed, succeeded to create buildings, such as the Xiangshan Campus and the Historical Museum at Ningbo, which deliberately reconnect with the invisible undercurrents of timeless Chinese imagery and traditions. These buildings do not echo any distinct formal attributes of the country’s rich architectural past, but they evoke atmospheres and moods that make one feel a depth of time and a grounded-ness in time and history. This sense of rootedness does not lie on any formal language or allusion, but the architectural logic itself, its cultural deep structure, as it were. This architecture also projects comforting and enriching experiences of participation in a meaningful historical continuum. The architect’s repeated use of re-cycled materials, such as old bricks and roof tiles, speaks of inherited crafts, timeless and selfless labour, and a sense of collective and shared identity, passed on to coming generations.

Visiting Wang Shu’s buildings made me recall Louis Kahn’s powerful Parliament Buildings in Dacca, which project an authoritative condensation of traditions, ageless and contemporary, geometric and mystical, European and Oriental. Kahn’s architecture in Bangladesh succeeds in giving a proud and optimistic cultural identity for a new Islamic state with ancient traditions, but extreme poverty today. These examples show that a respectful attitude to traditions does not imply regressive traditionalism, but its acknowledgement as a source of meaning, inspiration, and emotional rooting.

THE ECSTASY OF NEWNESS

The loss of the sense of historicity and evolutionary identity is clearly becoming a major concern in numerous countries developing at the accelerated rate of today’s aggressive investment strategies, expedient methods of construction, and universal architectural fashions. But, is newness a relevant aspiration and criteria for quality in art and architecture? Is a future without its constitutive past even conceivable?

Our ultra-materialistic and hedonistic consumer culture seems to be losing its capacity to identify the essences of life and experience, and to be deeply affected by them. Quality, nuance and expressive subtlety are replaced by such quantifiable properties as large scale, shock value, and strangeness. The uncritical interest in superficial uniqueness and newness is bound to shift the artistic encounter from a genuine and autonomous experience of the work into a comparative and quasi-rational judgement. Intellectual and commercial speculation replaces emotive sincerity, and genuine experiential quality is unnoticeably replaced by quantitative assessment.

Today newness is expected to evoke interest and excitement, whereas any reference to the traditions of the artform in question, not to speak of intentionally attempting to strengthen the continuum of that tradition, are seen as reactionary and as source of boredom. Already in the 1980s, Germano Celant, one of the Postmodern critics of the time, used such notions as “contemporaryism”, “hyper-contemporary”, “terror of the contemporary”, and “the vertigo of nowness” and referred to “a pathological and conformist anxiety […] that turns the present into an absolute frame of reference, an undisputable truth”3 . When thinking of the scene of art and architecture during the two first decades of the third millennium, we can speak of “a vertigo of newness”. New artistic projects keep emerging like an “unending rainfall of images”, to use an expression of Italo Calvino in his visionary Six Memos for the Next Millennium. 4

The constant and obsessive search for newness has already turned into a distinct repetitiousness and monotony; unexpectedly the quest for uniqueness seems to result in sameness, repetition and boredom. Newness is usually a formal surface quality without a deeper mental echo that could energize the work and its repeated encounter. The Norwegian philosopher Lars Fr. H. Svendsen points out this paradoxical phenomenon in his book The Philosophy of Boredom: “In this objective something new is always sought to avoid boredom with the old. But as new is sought only because of its newness, everything turns identical, because it lacks all other properties but newness”. 5 As a consequence, boredom with the old becomes replaced by boredom with the new.

Artistic newness is generally associated with radicality – the new is expected to surpass previous ideas in quality and effect and to throw prevailing conventions from the throne. But is there really any identifiable progress in art and architecture, or are we only witnessing changing approaches to fundamental existential motives? What is the quality that makes us experience a 25,000 year old cave painting with the same affect and impact as any work of our own day? Hasn’t art always been engaged in expressing the human existential condition? Shouldn’t art and architecture be oriented towards the timeless questions of existence rather than the appeal of the momentary and fashionable? Shouldn’t architecture seek the deep and permanent essences of human existence instead of obsessively trying to generate a passing experience of newness? I do not believe that any profound artist is directly interested in newness, or self-expression, for that matter, as art is too seriously engaged in deep existential issues to be concerned with such passing aspirations. “No real writer ever tried to be contemporary”, Jorge Luis Borges asserts bluntly, and the same surely applies in architecture.6 What contemporariness is there in the Pharaonic, Roman and Mughal architecture of Kahn, or the Aztek, Mayan and Chinese layers of Utzon’s architecture?

Newness is usually related with extreme individuality and self-expression, but self-expression is another questionable objective in art. Indeed, since the emergence of the modern era, art and architecture have increasingly been seen as areas of self-expression. Yet, Balthus (Count Balthasar Klossowski de Rola), one of the finest figurative painters of the late twentieth century, expresses a converse view: “If a work only expresses the person who created it, it wasn’t worth doing […] Expressing the world, understanding it, that is what seems interesting to me”.7 Later, the painter re-formulated his argument: “Great painting has to have universal meaning. This is really no longer so today and this is why I want to give painting back its lost universality and anonymity, because the more anonymous painting is, the more real it is”.8 Echoing the painter’s view, I dare to say that we also need to give architecture back its lost universality and anonymity, because the less subjective architecture is, the more real it is, and the more it has the capacity to support our individual identities. Conversely, the more subjective a work is, the more it focuses on the subjectivity of the author, whereas works that are open to the world and multiple interpretations, provide a ground of identification for others. Just think of the assuring sense of the real evoked by the anonymous vernacular building traditions around the world.

Balthus also scorns self-expression as an objective of art: “Modernity, which began in the true sense with the Renaissance, determined the tragedy of art. The artist emerged as an individual and the traditional way of painting disappeared. From then on the artist sought to express his inner world, which is a limited universe: He tried to place his personality in power and used paintings as a means of self-expression”.9 Again, the painter’s concern clearly applies to architecture, although architects rarely write about the mental dimensions in their work.

TRADITION AND RADICALITY

In his Harvard lectures of 1939, published as The Poetics of Music, Igor Stravinsky, the arch-modernist and arch-radical of music, presents an unexpectedly forceful criticism of artistic radicalism and the rejection of tradition: “The ones who try to avoid subordination, support unanimously the opposite (counter-traditional) view. They reject constraint and they nourish a hope – always doomed to failure – of finding the secret of strength in freedom. They do not find anything but the arbitrariness of freaks and disorder, they lose all control, they go astray[…]”10 In the composer’s view the rejection of tradition even eliminates the communicative ground of art: “The requirement for individuality and intellectual anarchy […] constructs its own language, its vocabulary and artistic means. The use of proven means and established forms is generally forbidden and thus the artist ends up talking in a language with which his audience has no contact. His art becomes unique, indeed, in the sense that its world is totally closed and it does not contain any possibility for communication.”11 The fact that Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was considered so radical at its time that the premier in Paris in 1913 turned into a violent cultural street riot, gives an added perspective to the composer’s view of the dialectics of tradition and artistic radicalism.

I wish to reiterate that newness and uniqueness alone are hardly relevant aspirations for art. Meaningful artistic works are embodied existential expressions that articulate experiences and emotions of our shared human condition and destiny. Works of art from poetry to music, and painting to architecture, are metaphoric representations of the human existential encounter with the world, and their quality arises from the existential content of the work, i.e. its capacity to re-present and experientially actualise and energize this very encounter. To be more precise: artistic works do not symbolize another reality; they are another reality. Great works of architecture and art re-structure, sensitize, and mythicize the experiences of our encounters with the world. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty significantly points out: “We come to see not the work of art, but the world according to the work”12 He also suggests that Paul Cézanne’s paintings make us feel how the world touches us. A fresh and sensitized articulation of the fundamental artistic issues gives the work its emotive power and life force. Constantin Brancusi formulates the artistic aim simply but forcefully: “The work must give immediately, at once, the shock of life, the sensation of breathing.”13 This master sculptor’s requirement also applies to architecture; an architecture that does not evoke sensations of life, remains a mere formalist exercise. When art is seen in its existential dimension, uniqueness as a formal quality loses its value.

Another modernist arch-radical, Ezra Pound, the Imagist poet, also confesses his respect for tradition as he points out the importance of the ontological origin of each artform: “…[M]usic begins to atrophy when it departs too far from dance […], poetry begins to atrophy when it gets too far from music […]”14 Similarly, in my view, architecture turns into mere formalist visual aesthetics when it departs from its originary motives of domesticating space and time for human occupation through distinct primal encounters, such as the four elements, gravity, materiality, verticality and horizontality, and the metaphoric representation of the act of construction itself; the process of building is a kind of a dance, the ballet of construction work. Architecture withers into a meaningless formal game when it loses its echo in the timeless myths and traditions of building. Instead of portraying newness, true architecture makes us aware of the entire history of building and it re-structures our reading of the continuum of time. The perspective that is disregarded today is the fact that architecture structures our understanding of the past just as much as it suggests images of future. Every masterpiece re-illuminates the history of the artform and makes us look at earlier works in a new light. “When one writes verse, one’s most immediate audience is not one’s own contemporaries, let alone posterity, but one’s predecessors”,Joseph Brodsky, the poet, asserts.15

CULTURAL IDENTITY

Cultural identity, a sense of rootedness and belonging is an irreplaceable ground of our very humanity. Our identities are not only in dialogue with our physical and architectural settings, as we grow to become members of countless contexts and geographic, cultural, social, linguistic, as well as aesthetic identities. Our identities are not attached to isolated things, but the continuum of culture and life; our true identities are not momentary attractions, as they have their historicity and continuity. Instead of being mere occasional background aspects, all these dimensions, and surely dozens of other features, are constituents of our personalities. Identity is not a given fact or a closed entity. It is a process and an exchange; as I settle in a place, the place settles in me. Recent neurological studies even show that our physical surroundings alter our brains.16Spaces and places are not mere stages for our lives, as space and mind are “chiasmatically” intertwined, to use a notion of Maurice Merleau-Ponty. As this philosopher argues: “The world is wholly inside, and I am wholly outside myself.”17 Or, as Ludwig Wittgenstein concludes: “I am my world.”18

The significance I am giving to tradition, not only as a general sense of cultural history, but also as the need of understanding the specificity and locality of culture, raises critical concerns of today’s careless practice of designing in alien cultures for commercial interests. As anthropologists, such as the American Edward T. Hall, have convincingly shown, the codes of culture are so deeply ingrained in the human unconscious and prereflective behaviour, that essences of culture take a life time to learn. Do we really have the right to execute our designs in cultures that are very different from our own, merely for our own economic interests? Isn’t this yet another form of colonialization? In this case, colonialization of identity and mind.

ARCHITECTURE AND IDENTITY AS EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES

Let me be clear, I do not support nostalgic traditionalism or conservatism, I merely wish to argue that the continuum of culture is an essential – although mostly unconscious – ingredient of our lives as well as of our individual creative work. Creative work is always collaboration: it is collaboration with countless other thinkers, architects and artists, but it is collaboration also in the sense of humbly and proudly acknowledging one’s role in the continuum of culture and tradition. Every innovation in thought – both in sciences and the arts – is bound to arise from this ground and be projected back into this most honourable context. Anyone working in the mental sphere, who believes that he/she has arrived at his/her achievement alone is simply blindly self-centered and hopelessly naïve.

Architectural and artistic works arise in the continuum of culture, and they seek their role and position in this continuum. Jean Genet, the writer, expresses touchingly this idea of presenting the work to the tradition: “In its desire to require real significance, each work of art must descend the steps of millennia with patience and extreme caution, and meet, if possible, the immemorial night of the dead, so that the dead recognize themselves in the work”.19 When a work of apparently extraordinary uniqueness is not accepted in this ever expanding gallery of artistic tradition, it will be quickly forgotten as a mere momentary curiosity. Our time is usually building such curiosities. On the other hand, regardless of its initial novelty and shock effect, even the most original and revolutionary work that succeeds to touch essential existential qualities, ends up reinforcing the continuum of artistic tradition and becomes part of it,. This is the basic paradox of artistic creation: the most radical of works end up clarifying and strengthening tradition. The Catalan philosopher Eugenio d’Ors gives a memorable formulation to this paradox: “Everything that remains outside of tradition, is plagiarism.”20 The philosopher’s cryptic sentence implies that works of art that are not supported and continuously re-vitalized by the blood circulation of tradition are doomed to remain mere plagiarizations in the realm of arrogant and pretentious newness. These works do not possess an artistic life force, and they are doomed to become mere curiosities of the past.

The most eloquent and convincing defence of tradition is surely T.S. Eliot’s essay “Tradition and Individual Talent” (1919), written nearly hundred years ago, but its wisdom has been sadly forgotten. The poet states that tradition is not a static “thing” to be inherited, preserved or possessed, as true tradition has to be re-invented and re-created by each new generation. Instead of valueing mere factual history, the poet argues for the significance of “a historical sense”, an internalised mental dimension. It is this historical sense that ties the artist and the architect to the continuum of culture and provides the backbone of his/her language and its comprehensibility. The fundamental issues of identity in terms of the questions “who are we” and “what is our relationship to the world” are constitutive. This historical sense also brings about collective cultural meanings as well as a societal purposefulness. It is this historical sense that gives profound works their combined humility, patience, and calm authority, whereas works that desperately aspire for novelty and uniqueness will always appear arrogant, strained, and impatient.

Although T.S. Eliot’s essay has been often referred to, I dare to quote its most essential message, which is more pertinent today in the age of globalization than ever before:

Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour. It involves, in the first place, the historical sense […] and the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write [and to design] not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature [architecture] [… ] has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order. This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and the temporal together, is what makes a writer [an architect] traditional and it is at the same time what makes a writer [an architect] most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his own contemporaneity.

No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead. 21

The poet’s arguments make it clear that creative work is always bound to be a collaboration, a collective effort of the artist with his/her contemporaries as well as predecessors. The views of the artistic thinkers, whom I am quoting in this lecture, also de-mystify the myth of the solitary and isolated genius. Great works of art and architecture cannot arise from cultural ignorance; they emerge in the midst of the evolving story of the history of the artform. The masterpieces emerge equipped with an unexplainable capacity for eternal dialogue and comparison.

TRADITION AND INNOVATION

I want to repeat that I do not wish to praise tradition because of a nostalgia for the past. Neither am I speaking about traditionalism as an alternative to individual invention, but about an embodiment of the essence of tradition and identity, as necessary preconditions for meaningful creativity. I speak about the value of tradition because of its fundamental significance for the course of culture and human identity, as well as for the arts, or any other creative endeavor. Tradition maintains and safeguards the collective and accumulated existential wisdom of successive generations. It also gives a reliable direction to the new and maintains the comprehensibility and meaning of the new. We can appreciate the genuinely new of our own time because of Dante, Michelangelo,and Shakespeare. At the same time, the masterworks of our time give new meanings to the masterpieces of the past.

It is evident, that artistic meanings cannot be invented as they are unconscious and pre-reflective existential re-encounters of primal human experiences, emotions and myths. As Alvaro Siza, the Portuguese master architect, has argued, “Architects don’t invent anything, they transform reality.” 22In the case of Siza himself, this attitude of humility has produced more lasting qualities in architecture than the self-assurance of his celebrated colleagues, who have deliberately adopted the role of radical formal innovators. The continuum of tradition provides the ground from which all human meaning arises. Architectural meaning is always contextual, relational, and temporal. Great works achieve their density and depth from the echo of the past, whereas the voice of the products of superficial novelty remain feeble, incomprehensible and meaningless.

THE GROUND OF CULTURE

Tradition is mostly a non-conscious system that organizes and maintains a sense of historicity, context, coherence, hierarchy and meaning in the constant forward flow of culture. A coherence of tradition is created by the firm foundation of culture, not by any singular and isolated characteristics or ideas.

The quick collapse of this collective mental foundation during the past decades is already a serious obstacle for education in the creative fields today. It is difficult, indeed, or often totally impossible, to teach architecture, when there is too little inherited tradition of knowledge in relation to which new knowledge could be understood. The fragmentation of knowledge into isolated facts and bits of information, due to the dominance of new digital search media, reinforces the lack of an integrating background of culture, and gives rise to a rapid fragmentation of world view. A wide knowledge of classical literature and arts has been a crucial ingredient of an understanding of culture as a background and context for novel thought and artistic creativity. How do you teach architecture and art when the mentioning of almost any historically important name or phenomenon is met with an ignorant stare? Our personal identities are not objects, they are not things; our identities are processes that build upon the core of an inherited cultural tradition. A coherent sense of self can only arise from the context of culture and its historicity.

In today’s publicized and applauded avant-garde architecture, formal uniqueness is sought ad absurdum at the cost of functional, structural and technical logic, as well as of human perceptual and sensory realities. Architectural entities are conceived as a-historical, detached and disembodied objects, detached from their context, societal motivation, and dialogue with the past.

It is likely that societies and nations do not possess a capacity to learn; only individuals do. It is sad to observe that city after city, country after country, seem to go through the same fundamental mistakes that others, slightly ahead in cultural and economic development, have already committed earlier. Particularly the ecstasy of wealth seems to blind societies, make them undervalue or neglect their own histories, traditions and identities. In the case of newly wealthy contemporary societies, it is as if, at the moment of sudden wealth, we would become ashamed of our past, regardless of its human integrity and quality of its settings. It is as if we would suddenly want to forget who we are and from where we have come.

What is at stake in the loss of the lived sense of tradition, is our very identity and sense of historicity. We are fundamentally historical beings, both biologically and culturally. It is totally reasonable to think that we are all millions of years old; our bodies remember our evolutionary past by means of the biological relics in our bodies, such as the tailbone from our arboreal life, the plica semilunaris, the point where our horizontally moving eyelid was attached next to our eye, from our Saurian life, and the remains of gills in our lungs from our primordial fish life.

In his book on slowness, Milan Kundera argues that forgetting is in direct relation with speed, whereas remembering calls for slowness.23 The obsessively accelerated change of fashion and life style makes an accumulation of tradition and memory mentally difficult. As Paul Virilio, the architect-philosopher has suggested, the main product of contemporary societies is speed. Indeed, two of the disturbing characteristics of the Post-modern era, according to philosophers like David Harvey and Fredrik Jameson, are depthlessness and the lack of an overall view of things.24

THE TASK OF ARCHITECTURE

The primary task of architecture continues to be to defend and strengthen the wholeness and dignity of human life, and to provide us with an existential foothold in the world. The first responsibility of the architect is always for the inherited landscape or urban setting; a profound building enhances its wider context and gives it new meanings and aesthetic qualities. Responsible architecture improves the landscape of its location and gives its lesser architectural neighbours new qualities instead of degrading them. Profound buildings are not self-centered monologues, as they always enter into a dialogue with existent conditions; Buildings mediate deep narratives of culture, place and time, and architecture is in essence always an epic art form. The content and meaning of art – even of the most condensed poem, minimal painting, or simplest house – is epic in the sense of being a manifestation of human existence in the world.

The fascination with newness is characteristic to modernism at large, but this obsession has never been as unquestioned as in our age of mass consumption and surreal materialism. Designed aging of products, as well as the adoration of novelty, are deliberate psychological mechanisms at the service of ever accelerated consumption. Architecture has also turned into a consumer product. However, these characteristics are also ingredients of today’s collective mental pathology. Also architecture is increasingly promoting distinct life styles, images and personality types instead of strengthening the individual’s sense of the real and of him/herself.

The task of architecture is not to create dream worlds, but to reinforce essential causalities, processes of rooting, and the sense of the real. The fascination with novelty is deeply connected with the self-destructive ideology of consumption and perpetual growth. Instead of contributing to meaningful and coordinated landscapes and cityscapes, the structures of today’s businesses (and almost everything is considered business in the world of fluid capital) turn into self-centered and self-indulgent commercial advertisements. Whereas responsible buildings are deeply rooted in the historicity of their place and they contribute to a sense of time and cultural continuum, today’s monuments of selfishness and obsessive novelty flatten the sense of history and time. This experience of flattened reality makes us outsiders in our own domicile; in the middle of abundance we have become consumers of our own lives and mentally homeless. We have even become alienated from ourselves. Yet, as Aldo van Eyck, the Dutch modernist architect, insisted: “Architecture should facilitate Man’s homecoming.”25

Great works possess a timeless freshness and they present their embodied enigma always anew as if we were looking at the work for the first time: the greater the work is the stronger is its resistance to time. As Paul Valéry suggests: “An artist is worth a thousand centuries”.26 Newness has a mediating role in revealing the existential dimension through fresh and unexpected metaphors. Only in the sense of the perpetually recharged and re-energized image, timeless newness is a quality in artistic and architectural works. This is where also anonymity turns into a specific value. Such works constitute the realm of tradition and they are reinforced by the authority and aura of this continuum. I personally like to repeatedly revisit certain masterworks of painting and architecture, and re-read my favourite books to find myself equally fascinated and moved each time. I have had the fortune of visiting the legendary Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto in Noormarkku, Finland (1937-39), numerous times during half a century, but at each new visit this architectural miracle welcomes me with the same freshness and a stimulating sense of expectation and wonder. This is the power of a true artistic tradition that halts time and re-introduces the already known with a seductive new freshness and intimacy. This is also the kind of architecture that empowers us and strengthens our sense of being, identity and dignity.

In our age… there is coming into existence a new kind of provincialism, not of space, but of time; one for which history is merely the chronicle of human devices which served their turn and have been scrapped, one for which the world is the property solely of the living, a property in which the dead hold no shares.27

This article is an edited version of Juhani Pallasma’s speech at The Bengal Institute in Dhaka in November 2016. We would like to thank the Author for his permission to publish.

Translation from Polish: Dorota Wąsik