The church at Olcza in Zakopane versus the Cracovian school of regionalism

Each whole makes a form and every form is a whole.

Form is not a sum of its parts, it is more than that.

Form depends on the relationships between the parts and the whole.

Form is a unity of many variables.

The form, once it becomes a part of a larger whole, loses its individuality in favour of the whole.

The form depends on the whole in which it is to appear.

The form, when changing, will change the whole of which it is part, and it will change all the other parts which make up that whole.

Juliusz Żórawski

O budowie formy architektonicznej, 1962

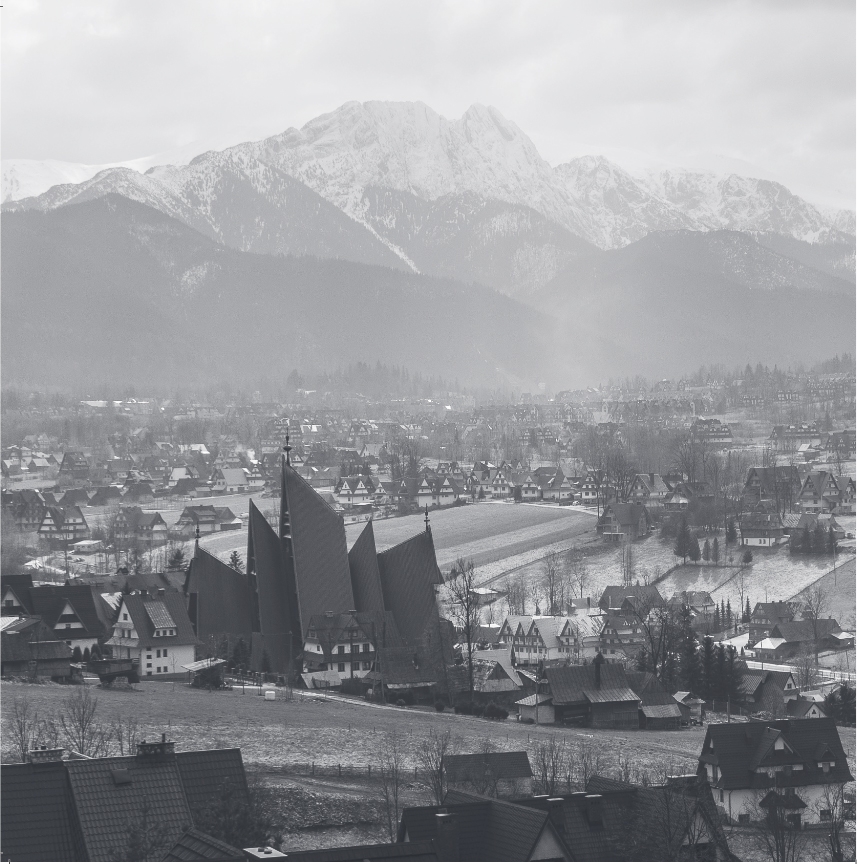

Olcza is a district of Zakopane, situated away from the touristy centre of that highland town. It does not stand out as anything special amidst the typical built environment found in the Podhale region. Homes and hotels with high, multicoloured roofs and architectural details that often look like a mockery of Witkiewicz’s Zakopane Style, are chaotically scattered all over the hills, as if they have spilled out of a big sack. It is also typical that the church occupies an important place within the space of Olcza. It is not only an important place for the local community, but also an attraction on the map of religious tourism, the latter being quite popular in the Podhale region. Unfortunately, in the cacophony of the surrounding space, the following fact gets overlooked: namely, that the church at Olcza, or the Marian shrine of the priests of the Missionary Order, designed between 1977-1981 by a married couple of Crakovian architects, Tadeusz Gawłowski and Maria Teresa Lisowska-Gawłowska, is a unique building, one of the most interesting, noteworthy, and consistent examples of regionalism in Polish architecture, created as a result of not one, but several interwoven traditions.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN KRAKÓW AND ZAKOPANE

The relationship between Kraków’s architectural milieu and the Podhale region is one that has made a strong impression on both of their cultural identities. It has been cultivated since the middle of the 19th century, when Tytus Chałubiński began popularizing highland tourism and the health-enhancing qualities of the Zakopane climate. The way of thinking about the Podhale region, typical for the Młoda Polska movement, and rooted in the romantic tradition of thinking about Podhale and its inhabitants, mythologizing (and in many instances, also orientalizing) the wild nature of the Tatra mountains and the strength of the highlander’s (góral) character, has survived – albeit gradually diluted – until the present day. The relationship between Kraków and Podhale is undoubtedly mostly geographically based: for the inhabitants of Kraków, the Tatra Mountains provide a natural escape from city life, while Kraków is the nearest large urban and academic centre accessible to the dwellers of Podhale. Therefore it is not surprising that the design of regional architecture, generally understood in this case as highland architecture, played an important role in the teaching programs and curricula of the Kraków Polytechnic, established in 1945. Interest in regionalism was further enhanced by the proclamation of socialist realism in 1949. Regionalism, which allowed for a free dialogue with tradition and which situated itself on the margins of major political tensions, became one of the two popular ways of escaping the doctrine. The other was industrial architecture – pragmatic, in its very nature devoid of decoration, and able to draw the most from the achievements of prewar functionalism. Both of these paths intertwined, creating a theoretical and formal basis for the creation of the Gawłowskis’ church in Zakopane.

THE KRAKÓW POLYTECHNIC

In 1945, Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, the founding father of Kraków’s Faculty of Architecture (initially operating in affiliation with the the Mining Academy), invited to join him in setting it up, among others, two Kraków-born graduates of the Warsaw Polytechnic: his former pupil from the time when he taught architecture at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, Włodzimierz Gruszczyński and Juliusz Żórawski, an eminent modernist, who in the same year completed his doctorate, written under the supervision of Władysław Tatarkiewicz, titled O budowie formy architektonicznej [On the construction of the architectural form]1 . The latter dissertation, published almost two decades later, today enjoys the status of a canonical work in the theory of architecture of the twentieth century, introducing an in-depth, multithreaded psychological perspective into the design field.

Although Szyszko-Bohusz never counted himself among the aficionados of the Zakopane Style, his pietistic attitude towards the architectural context (let us remember that the Faculty of Architecture was originally located on the Wawel Castle hill) was a lesson for Gruszczyński; a lesson that made a mark that remained apparent throughout his further professional life. Gruszczyński learned contextualism, based on an impression of space, over the next few decades – from 1956 he was the head of the Department of Designing in Landscape, later renamed the Department of Regional Architecture Design. Although Gruszczyński’s activity was one of the important sources of inspiration for the church project in Zakopane, it was not the greatest influence on the shaping of Tadeusz and Teresa Gawłowskis’ creative attitude.

Associated with the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, Teresa Lisowska-Gawłowska, an architect by education, remained at her husband’s side in a manner typical of her time – as an invisible assistant – and she often dealt with interior design, perceived back then (and sometimes even today) as a “feminine domain”. This was also the case with the church at Olcza. She hardly ever wrote about architecture. Tadeusz Gawłowski did, though – always trying to present his wife’s contribution to the design process fairly – he published self-commentaries on their joint work. One should assume, however, that they both put themselves in the same place on the map of various traditions of architectural thinking. Tadeusz Gawłowski was a student, a collaborator, but also an “heir” of Juliusz Żórawski, both at the intellectual and design, and institutional level. After the death of Bohdan Lisowski, who had been Żórawski’s successor as the head of the Industrial Design Department, (he was also Teresa’s brother, and therefore Tadeusz Gawłowski’s brother-in-law), Gawłowski himself took over the unit in 1992. He repeatedly stated that his goal as an educator – in addition to adhering to the Vitruvian triad – was to teach design in harmony with his master’s concepts. He also professed and followed the same credo as a designer. Hence, the church in Zakopane can be considered the materialization of Żórawski’s theory – especially his concept of “virtuous continuation” and the shaping of “cohesive” or “unconstrained” forms depending on contextual conditions – in the architectural practice grounded in empirical experience.

UNCONSTRAINED FORM

Looking at the church from a distance, you can see the different ways in which it was embedded into the landscape, depending on which of the Olcza hills the observer is looking from. Seeing the building from the west, with the Tatra Mountains behind us, and some distant, scattered buildings in front of us, our attention is drawn to the fact that the work of the Gawłowskis, despite its bulk and cubic capacity incomparable with any other structure in the vicinity, and despite its prominent location on the slope, does not overwhelm the neighbourhood. It is an additional yet a matching element, reminiscent of a single stone lying among gravel. The incorporation of the temple into the countryside’s built environment was one of the important assumptions of the design, and this effect was achieved through the fragmentation of the solid into smaller segments, corresponding to the scale of the surrounding houses, and through the preservation of the traditional angle of sloping “roofwalls”. When we find ourselves in the north, we see that the dynamic and “chopped up” silhouette of the church, in whose lines the ridges deviate from the straight horizon, renders the directional tensions of the Tatras. It looks like yet another mountain, another element of the landscape.

Thus built, the architectural form, fragmented, and organic, constitutes a complete realization of the “unconstrained form” advocated by Żórawski for the environment of highly valuable natural qualities, which allows for the features of nature to be emphasized and extracted, always presenting free, unconstrained forms. The aim of the “unconstrained form”, unlike the “cohesive form” (compact, strong, unambiguous, monumental, towering over the environment), is – to use the language of painting – to remain as a figure merged into the background, or – in the language of music – to be one of the humble choristers instead of a soloist. What is more, the breaking up and vagueness of the form not only allowed it to be adapted to the surrounding conditions, but also meant a willingness to change in the future. “Architecture” – Żórawski wrote – “works only by adding or subtracting parts from previously given wholes”2. This “previously given whole”, consisting of elements belonging both to the world of nature and culture, is a landscape, which he called the mother-form. The architect should listen to what the mother has to say to him, and respond to her with the form of his architectural design. Clearly, the Gawłowskis listened to the “mother-Olcza” carefully and attentively.

VIRTUOUS CONTINUATION

In addition to the aspect of formal inclusion in the character of the environment, it is equally important that the temple is placed within the local architectural tradition, so markedly characteristic in the case of Podhale. The body of the church in Zakopane is a development of the idea realized by the Gawłowskis earlier on in the design for a much smaller parish church in the village of Rudy-Rysie, designed in 1965 and erected in 1966-1976. The echoes of the solutions developed by Tadeusz Gawłowski in the designs for thermal power plants in southern Poland are also resonant. In spite of this, the “Zakopane character” of the church at Olcza remains clear, even though it is based on impressions and perceptions rather than anything else. The architect maintained that the creative continuation of cultural traditions was the best way of nurturing the quality of contemporary sacred architecture, which of course also constituted a continuation (including at the level of applied terminology) of Żórawski’s thought. It is this “virtuous continuation”, based on finding the basic general guideline of an architectural prototype, that was to equip the form with the content, and build its symbolic layer – necessary in the case of a church because of the psychological and emotional needs of its users. Losing this guiding principle, abandoning a certain basic, original local quality in a derivative form, is the cardinal error of an architect who wishes to be faithful to the principle of “virtuous continuity”.

From a distance, the church designed by the Gawłowskis manifests its “Zakopane qualities” in the proportions of the body and the angles of the roof, taken from the traditional architecture of the Podhale area, and up close, with the details and materials used. Dialogue with the locality has been carried out here on several levels, starting with the interweaving of the “old” folk tradition with the “new tradition” – of modernism, ending with postmodern quotations. The architect repeatedly quoted Le Corbusier, saying that “architectural activity consists in adding parts to an already existing whole.”3 He maintained that the use of Le Corbusier’s Modulor as the basic metric system in the design was appropriate for the Zakopane context, because a similar system, based on the dimensions of the human body: feet and elbows, is typical for traditional folk structures therein. He combined the principles of proportions promoted by the aforementioned Włodzimierz Gruszczyński with the “silver division” found in the traditional, single-towered timber churches of the Podhale region. The layout of the temple at Olcza, on the other hand, departs from the long-standing local tradition. We are dealing with a single-space, focusing interior, without any side aisles or chapels, but with shallow annexes, creating space for individual prayer. It is the most popular pattern in Polish religious architecture of the 1970s and ‘80s. The architects entrusted the casting of the concrete skeleton of the church (allowing for so much span in the interior space) and the execution of the timber structure to local carpenters from the village of Piekielnik, pre-adapting the project to their limited technological possibilities and to the manner of erecting churches, typical of the 1980s – that is, using the “household” method. The church was equipped with gravitational ventilation, operating on a similar principle as the cooling towers previously designed by Gawłowski for a power plant, accelerating the exchange of air. Highly refined church acoustics also required thoughtful and clever solutions, taking into account the omni-directional propagation of sound: from the altar in the chancel, from the choir and the pipe organ, and from the congregation gathered within the space of the main aisle.

Against the background of these solutions, which creatively transformed the architectural tradition of the region, and at the level of artistic expression that operated in simple modernist forms, there is another, very distinctive and very literal “Zakopane-esque” citation, namely the so-called “dźwierza”: the decorative, ornamental doorway, with metal rivets and forged door handles. They lead into the temple and enclose the altar wall, building the narrative symbolic system of the church as an intermediate place between the temporal and the eternal; at the same time, the architects are thereby paying tribute to the traditional regional craftsmanship and introducing a kind of link to the past. Located in the vestibule of the church, the original, historic door from the Olcza area acts as a “witness of history” and constitutes the architectural form (as developed by the Gawłowskis) as an extension of tradition.

THE FREEDOM OF FORMING (SIC!)

The Gawłowskis were designing in an intelligent way, consciously and with premeditation, as well as – very importantly – with exceptional artistic sensitivity. Work on each of their projects was preceded by the so-called “abstracts” – miniature abstract sculpture or graphic forms, which Teresa Gawłowska introduced to her teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. The idea of form-shaping, contained in these abstracts, provided a formal guideline for the whole further design process, being another instance of “virtuous continuation” – not of the architectural tradition or the urban context, but of the first thought and gesture of the designer. Initiated at the “abstraction stage”, the process of integrating the various arts was to culminate in the creation of a building in which the architecture, sculptural in its form, as well as the wall paintings, stained glass windows, architectural details and fittings would be merged together, coherent and unbroken – as in the Gesamtkunstwerk idea. The project assumed that the “roof-walls” of the main aisle would not be covered in plaster, and the pattern of imprinted formwork boards would remain on their concrete surface – as a tactile testament to the architecture originating from nature. Rather than the white paint that we see today, they were to be covered with paintings executed directly on raw concrete, composed between the horizontal divisions of the planes (which Teresa Gawłowska used to call “the Hosanna”) and designed by her. They were never realized, and neither were the stained glass windows designed by the architect. Also never completed were the door frameworks intended to constitute a free-standing arcade in front of the main entrance to the church. During the implementation, some other changes were also introduced to the project – inter alia, to the form of the confessionals, benches for the congregation, the mensa, the tabernacle, the pulpit, the pipe organ, the railings, and the colour of wood cladding – compared to those originally designed by the architects. However, as Gawłowski wrote, without trying to hide his regret, the most painful departure from the original project in the case of the church at Olcza was the change in the divisions of the windows, which were originally designed – as in Rudy-Rysie – in the pattern of a honeycomb, constituting a “neutral raster” rather than a “pseudocomposition”.

The Missionary Church in Zakopane has been repeatedly transformed and repaired over a period of almost forty years, and each such repair project has robbed it of some aspect of its original shape. Today it is surrounded by a car park, statues and information boards, while its interior is being overcrowded – despite visible efforts to preserve some semblance of stylistic coherence – with further furnishings and decorations. The fact that the church architecture passes the test of time regardless is the best testimony to the power of its form.

Translation from Polish: Dorota Wąsik