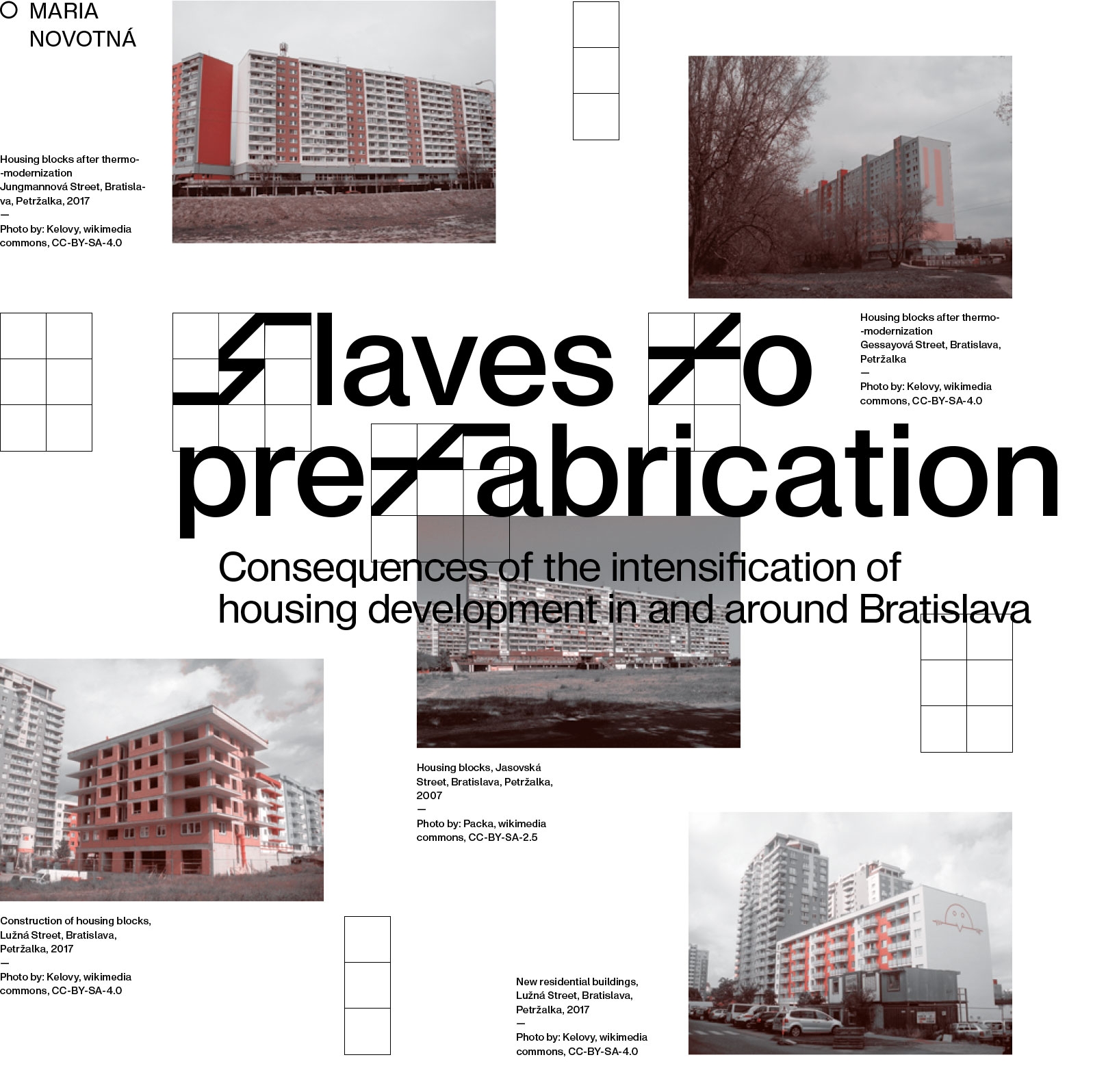

Consequences of the intensification of housing development in and around Bratislava

Mass construction of housing estates in Bratislava

After World War II, Bratislava had thirty thousand apartments.1 Despite the efforts of progressive architects, the housing stock was largely deprived of sufficient sanitary facilities. The city became depopulated, and the socialist regime applied its concept of planning and collectivization – among other things – also to housing development in Czechoslovakia. After the abolition of private ownership and the nationalization of land, market prices ceased to apply, but unrestrained spatial development of cities began: the existing urban structures were interfered with or replaced with new buildings. Intensive post-war modernization of various areas of life was conducive to urbanization, and the planning of housing development required the state to create institutions focused on research, design, and implementation of projects.2

The authorities pushed for quantitative efficiency of the construction industry, and the response was an intensive development of prefabrication. The rapid population growth in urban centres commanded the creation of flexible construction companies that would offer diversified urban solutions, and at the same time would provide a level of comfort in various types of apartments in line with modern expectations. Efforts to increase the number of flats have resulted in the prefabrication of several standardized forms of a tower block. The state-financed construction of prefabricated blocks of flats responded to the needs of the changing demographic structure of the city – in a period of forty years, apartments for over three hundred thousand people were built in Bratislava.3

It is because of this high number that we called it mass construction rather than social housing. In a classless society that the socialist regime tried to create, the socially weaker class was simply not meant to be. Mass construction and the influx of people from other regions of Slovakia resulted in breaking the cultural continuity of the city.4 Nowadays, while criticizing all that is associated with the past regime, we unconsciously reject the valuable urban structures that had been created in that era. I am not driven by nostalgic optimism or the indiscriminating praise for spatial planning of the last century. I merely wish to compare concepts and tendencies that we suppose indifferent to the quality of living today. The centralization of Bratislava’s function as a capital in the last century, and the lack of a motorway connection to Košice, the main metropolis of eastern Slovakia and the second largest city in the country, have led and continue to lead to a constant influx of new residents and a permanent housing shortage. Apartments offered on the market meet only the basic demand, whereas their quality and size turn out to be of secondary importance. Residential units meet only the minimum requirements in terms of standards and norms, and they are built as cheaply as possible. We are falling into a vicious circle: new residents do not establish ties with the city, and the city does not offer them a living space that would foster a bond. As a result, the immigrants perceive the metropolis only as a source of income, rather than a place to live.

Intensive housing development yesterday and today

Until 1968, mass construction occupied all areas suitable for building housing estates, i.e. flat plots of land, without spatial barriers or the pre-existing buildings. Subsequently, the constant influx of new residents forced the development of urban projects also in less favourable locations: in hilly terrain, outside the city limits, or within the existing urban structures. The necessity to economically manage financial resources, the problems with operating machinery in more hilly terrain or between the existing buildings, and arguments related to the need of maintaining agricultural land slowed down the development.5 The optimal solution was to increase density of the planned housing estates, but urban concepts were often implemented in part only. Increasing the density of buildings continues to this day, and is not accompanied by any attempts to draw conclusions from previous experiences. The efficiency of infrastructure and the provision of services are still inadequate compared to the needs of the current and future residents.

Contemporary intensification is not only about increasing the density of urban structures and reducing the amount of green areas. Where the construction of underground car parks seems too expensive, part of the land is allocated to aboveground parking lots. At the same time, in houses with underground car parks, the layout of the apartments depends on the structure of pillars and load-bearing walls of the car park. Extensions are also built – extra floors added on to the existing multi-family houses.

New buildings and extensions attempt to meet the demand, but they do not offer comprehensive solutions to the problems related to living in the city. Private real estate development companies carry out their projects mostly in order to sell or rent flats and commercial spaces; activities aimed at the development of the city as such are outside their purview. They understand their contribution to the city’s development as creating projects of unique visual quality. In terms of size and interior layout, the apartments offered in these buildings are barely within the norm. A walk around Bratislava is like watching an egocentrics’ parade where the combination of materials and designs rubs shoulders with tacky details, soulless emptiness, and a lack of genius loci. The local government is only gradually developing tools that will allow them to compel private developers to include public services – for example schools and kindergartens – and the development of public infrastructure in their investment projects.

All the above-mentioned processes, combined with changes in the law, have recently caused a disaster in the transport infrastructure. Since 2009, the edges of the streets have been littered with cars. Since new law allowed parking on pavements in the capital, there has been practically no space left there for pedestrians. In addition, the parking space density index, enshrined in the law, designates the obligatory one parking space per apartment. The direct effect of the increase of pseudo-residential space was the increase of the number of people who live in Bratislava but are not registered there as residents. As a result, the local government ran out of financial resources for the city to function like other European metropolises.

At the same time, the inhabitants of the concentrated city of Bratislava have become experts on parking. Housing estates built in the late 1970s on hilly terrain taught the migrants from lowlands how to park on steep streets. In modern housing estates, people handle it differently: they double park and don’t apply the handbrake. If a car is blocked, its driver will simply push away the ones that are blocking it. In addition to allowing time for the typical morning traffic jam, we must therefore add at least half an hour needed to free up or find our own car, because it could be standing up to two hundred meters from the place where we parked it a few hours earlier.

In the second half of the twentieth century, efforts to develop efficient and economical buildings resulted in prefabricated housing estates. Prefabrication was invented in order to eliminate the wet process – pouring concrete – from the construction site, which was meant to speed up the work. The walls were lined with wallpaper, the floors were laid with linoleum. These materials were subject to centralized production and appeared in a limited number of patterns, so the unification of the interiors grew even deeper. At that time it was a new technology, the builders were only just learning how to use it, therefore many low-quality houses were put into use. In a situation where the architects did not have enough time or financial resources to create detailed documentation regarding the finishing works, the choice of finishing materials and aesthetic solutions turned out to be the combined result of the taste of the foreman of the construction crew and circumstance.

After collectivization came privatization and freedom of expression. In the 1990s, central planning ended and the owners began to make decisions about the appearance of their houses. The period of extensions and thermal modernization began. The lack of cultural continuity, the indiscriminate elimination of prefabrication from the life of Slovaks, getting rid of prefabricated housing estates and everything that was associated with communism, combined with the extremely effective marketing of companies dealing with thermal modernization, gave rise to mass trend of painting the uniformed housing estates from the last century. Thermal insulation became an indispensable element of any renovation, a way to improve the quality of housing and a showcase product of capitalism. The marketing was based on presenting thermo-modernization as an investment that would make it possible to save on maintenance costs in the future, but its negative side-effects were ignored (attaching polystyrene to an uneven, brittle base promotes the appearance of mould; amateurish fixing causes the insulation to move away from the wall, which reduces its effectiveness; shoddy finish does not drain moisture, it collects dust and is an ideal substrate for fungi). The polystyrene insulation system had practically been promoted to the rank of a norm in building renovation. In housing estates, criticized for their uniformization, a standardized and simple solution was used, which was supposed to be the answer to many problems at once. Thermo-modernization was sold as a treatment to the “trauma of socialism”: the monotonous homogeneity of neighbourhood façades turned into a palette of pastel colours and geometric patterns.

This new, fluid identity was created by thermo-modernization companies without aesthetic education, by painting crews, and by mere chance. Today’s smooth, faultless, industrially manufactured plasters reflect the residents’ longing for an ideal, carefree world. Yet their lives and the interiors of their apartments are many coloured, full of various tones and irregularities. As Slovak architect Ivan Matušík put it: “All things live their own lives, including mistakes.” We try to hide the mistakes behind a false idea of perfection. The apartment block insulated with polystyrene, painted in bright colours, responds to the problems of the post-communist society. The inhabitants are no longer surrounded by the greyness typical of the past regime, and they feel that they can make independent decisions about their property, invest in it, and adapt it according to their own ideas. In dreams of a small investment that would reduce the cost of living, confronted with its amateur and low-quality workmanship, we see a reflection of present times and the priorities of contemporary people.

Changing the interior of apartments after privatization

Since the 1960s, the standardized layout of typical apartments has been enriched with an innovation in the form of a prefabricated, complete interior with kitchen furniture and corner dining space. Unified products, such as Umakart HPL modules,6 are difficult to assess in terms of aesthetics or quality of the materials and objects used – they were installed in the apartments as a result of centrally planned production. A separate toilet is a plus, but due to an unfortunate planning solution, it was combined with a walk-through bathroom. This solution provokes reflection on the importance of caring for the body and privacy. Apparently, there was no excessive emphasis on intimacy in the family, and no taboo on nudity.

The new owners of the privatized flats were eager to interfere with the interior layout. In the first place, they usually got rid of the plastic boards and replaced them with masonry structures, and then with drywall (plasterboard). Many renovation companies still offer the dismantling of Umakart panels. The removal of the Umakart bathroom is considered an upgrade that increases the price of an apartment by approximately 10 per cent.

Before the introduction of laminated kitchens and bathrooms, the socialist regime tried to encourage the use of canteens in schools and workplaces. The kitchen and dining room were not considered an essential part of the apartment. It was believed that families are satisfied with meals made of semi-finished products, and “the modern food industry and collective eateries provide services that have freed working women from tiring and unpleasant labour.”7 The kitchens were therefore small, often dark and not ventilated, placed in the farthest corner of the apartment. The departure from the mass nutrition model resulted in the production of ready-made, prefabricated laminate modules, identical in the kitchen, the bathroom and the hall, as well as the emerging belief that eating meals together strengthens family ties. The press in the 1960s clearly appreciated not only the kitchen as a full-fledged room, but also as a symbol of the position of women in society. For the next thirty years, kitchens gained large windows and a dining corner. They were situated progressively closer to the living room, later with just a door between them.

With the advent of capitalism, emancipation and privatization, also this last barrier has disappeared. The kitchen has become an inseparable part of the living room, whether this was due to the reorganization of interiors in the old apartments, or as an integrated module in new buildings. At the same time, however, modern standards do not treat the kitchen as a living room. It is stuffed into the back of the apartment, where the light from the rooms does not enter, or on one of the walls of the living room, usually the one farthest from the window, which further degrades the function of the kitchen. This solution does not separate family members who are preparing the meal from those who are spending time in the living room. In new designs for apartments or single-family houses, often offering a typical interior layout, the average size of the kitchen area has not increased over the last thirty years. If the optimization of the interior layout and the minimization of the space – as far as it is possible within the norm – continues, we will soon have to cook in windowless kitchens. Underestimating and disregarding the kitchen leads us to the question of whether we still consider cooking together as a family to be superfluous, and whether we will be content with the alternatives in the form of fast food and semi-finished products offered by the neoliberal system.

The interior layouts of apartments in tower blocks changed the most in the 1960s, also thanks to prefabricated interior finishing modules. Until the 1960s, it came as no surprise to anyone that the living room also served as a bedroom. The designers of the new housing estates had ambitions to raise the standard of flats and allocate a separate space for sleep, thus making life easier for the residents. There were standards and indicators for the number of square meters and additional space allocations (a cellar, a storeroom or a basement) per tenant. The modern trend of reducing the size of apartments has led to a situation where basements are an above-standard privilege, and entrance corridors are door-wide. There are doubts as to whether the bedroom has to be a separate room, and in cramped apartments there is often not enough space for a piece of furniture that would be intended only for sleeping. A separate bedroom, or even a space where a bed can fit, is now considered a luxury. The market price of an apartment with a bedroom is now about ten times the price at which it was built.

Apartment on arable land

In today’s Bratislava you won’t find any flats for rent or social housing.8 People fresh out of college or those who migrate to the city for work sublet apartments from private owners; therefore, the city does not regulate the price, only the free market does. The continuous growth of prices often forces tenants to share a flat. Even if there are still some standards and minimum requirements for housing in the designing process, in reality they are not being followed. Having too many tenants constitutes a form of intensification; this, in turn, reduces the quality of the apartment, but also of the environment. Public services and transportation become inefficient. Traces of Slovakia’s centralization and the role of Bratislava played in the last century are still visible. People from the eastern part of the country are constantly flowing into the capital, and consequently there is a shortage of housing. New residents often spend only their working days in the city, and do not develop a deeper bond with it. They are not interested in its history; the cultural continuity has been broken.

One element of Bratislava’s identity grew out of the discontinuity and the random, collage-like urban development. This city consists of a mosaic of (non)urban concepts complemented by a mixture of construction permits, assorted new building façades created by various architects, extensions, renovations, and old housing estates “tweaked” and “upgraded” by thermo-modernization companies. This hybrid is gradually joined by satellite housing estates, urban concepts of living in single-family houses on the outskirts of the city. It is difficult to tell whether young families move out of the city in order to achieve their dreams of their own garden, or whether they are looking for a cheaper alternative to living in the capital. Small houses with a plot of land in suburban municipalities are roughly 30 per cent cheaper than similarly sized apartments within the city’s administrative boundaries. However, it is difficult to speak of the benefits pertaining to the comfort of living in a single-family house, the way we used to imagine it. Problems are generated by contemporary spatial planning, which enables the creation of agglomeration clusters. Seemingly they look like a whole, an urban organism, but they were created without a plan, they lack services, adequate infrastructure, or public spaces: a market square, playgrounds, green areas. Their designers are selling a compact “American dream”: a single-family house on a small plot separated from former agricultural land, again with the minimum parameters required by the housing standards. The advertised garden is in fact limited to a patch of land enclosed by a tall, prefabricated fence. The immediate proximity of the neighbours does not allow you to enjoy the rural idyll or the privacy that you desire.

The standards, which are constantly lowered to the limits of reason, hinder flexibility in designing the interior layout and prevent the use of the potential that the house usually offers, for example having windows on all sides. The crowded plots of land and the small gaps between the houses prevent windows from being placed on the walls facing the neighbour’s plot, which forces the optimization of interior layout, similar as in the ordinary city apartments. Roads with the minimum required width and the lack of parking lots mean that also here the sidewalks are densely packed with cars. People who are stuck in the morning and afternoon traffic jams experience first hand the neglect of the issue of transport infrastructure, and its results.

The estates of single-family houses on the outskirts of cities consist of individual projects, usually erected on the basis of a ready-made design purchased from a catalogue, or they are developer-built, typically according to a unified pattern. The interior design is no longer the result of central planning, but it is still an industrial product; its choice often depends on the decision of the designer, and not the owner. In the “standard finish” only the pattern of flooring has changed over the course of thirty years, while other elements remained uniform and fixed. The lack of public spaces, parks and playgrounds is not conducive to the socialization of different age groups, but some time will pass until we see the consequences of living confined between prefabricated fences. The privatization of all available land also results in reducing the public space to a minimum – the communal space that the investor or the developer should take care of, in theory.

Slaves to prefabrication

In the years 1950–1982, 116,350 apartments in blocks of flats were designed, and they were built by 1995. Over 300,000 inhabitants moved into these apartments.9 The Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic reports that in the 1990s, about 380,000 people lived in Bratislava, of which about 80 per cent in prefabricated blocks. Currently, Bratislava’s local government reports that there are 223,000 housing units in the city,10 which means that 106,650 of those have been built in the last thirty years. According to these sources, it was estimated that the number of Bratislava residents was going to double since the 1990s, but the official data of the statistical office indicates 427,734 inhabitants in 2017. Meanwhile, researchers from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the Comenius University in Bratislava counted that 630,000 SIM cards are active in Bratislava at night.11

During the socialist period, thanks to state investments, 116,350 flats were built, plus 106,650 flats in the private sector, without state funding. The municipality reports that 1 per cent of flats within its area belongs to the city. These are 2,335 flats for rent, of which 878 are administered directly by the municipal office, and the remaining ones are administered by district offices. The average waiting time for such an apartment is seven to eight years.12

Recently, Bratislava changed its housing policy and decided to build apartments for rent. Architectural and urban planning competitions have been announced for specific locations, and there are also plans to renovate decaying buildings and revitalize wastelands in order to create communal apartments. A contemporary alternative to once affordable housing is a shared flat, rented from a private owner; another option is to purchase a cheaper property in the outskirts. The most popular houses are those from the catalogue of ready-made designs, typically surrounded by a high concrete fence. And so we remain slaves to prefabrication.