‘Archetype of a sorrowful divorce, work of disobliging death’

In his description of the funeral of his saintly brother Robert Cardinal Bellarmine, which took place at the beginning of the 17th century, English Jesuit Wiliam Coffin was amazed to discover a lack of any distance with which Italians treated bodies of their dead. He was particularly shocked at the proceedings while the body was being embalmed, and church hierarchs and aristocrats were on their knees hoping to get Bellarmine’s blood or internal organs for relics rather than praying for his soul. He was astonished to see droves of common people crowding the church and the bier in order to touch the dead Jesuit’s body and kiss his face or his feet.

In Coffin’s homeland and all over Europe beyond the Alps even saintly corpses inspired some dread and disgust. That is why they were promptly wrapped in shroud and buried in coffins, and were thus taken away from people’s sight. Even saints’ relics were kept in silver chests instead of being exhibited, like in Italy, in glass or crystal urns. It may have had to do with poor skills of north European embalmers; several dozen hours after their treatment bodies of Polish kings of the House of Vasa started to decompose so intensely that they had to be closed in coffins without delay. These masters could not show off their skills too often because the dying wished in their wills ‘not to have their bodies eviscerated’. Public presentation of the dead was regarded as an improper manifestation of pride, which can be exemplified by Teodor Beza’s description of the end of John Calvin’s life, ‘Many wanted to see the [deceased’s] face, not leaving him in peace either dead or alive, and among them there were people of other nationalities who had come from afar to look at him […] They greatly desired to see him even in death and they begged for it, but he was wrapped in shroud in order to prevent slander’.

It was only the family and closest friends who were given the possibility to pay a last tribute to the body directly; the majority of mourners were able only to look at the tightly shut coffin. A certain substitute for closer contact with the departed were paintings which showed his likeness but which were free of any drastic postmortem changes and signs of decomposition.

There are grounds to believe that having such a picture painted was a common pre-funerary practice at homes, and it was an indispensable element of the order of the day, described for example in Imrich Turzon’s diary, whose author wrote in great detail about the last tribute to his father, Gyorgy, on the Orava Castle. Gyorgy died on 24th December 1616; on 4th January the order of the funeral day was decided at a family gathering; on the next day the last will was opened, on 8th January a coffin upholstered with black cloth was brought so that the body could be deposited there the next day. Just before it happened, the deceased’s wife had commissioned a painter to make sketches for a likeness of Turzon on his deathbed. The painting was completed within a month and was displayed during the funeral on 14th February 1617. Unfortunately, the way that the painting was displayed during the ceremony was not described. It may have been incorporated into the ornamental bier, just like a likeness of King Władysław IV on his deathbed, seen on the design of his castrum doloris by Giovanni Battista Gisleni. It is known that after Gyorgy Turzon’s funeral, his post mortem portrait was hung in the chapel at the Orava Castle as his temporary tomb, and when a sumptuous stone monument was erected, it was transferred to a temple in Turzon’s other residence in Bytca, as a unique cenotaph and memorial to the late baron.

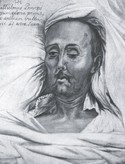

It was possible to execute Turzon’s postmortem portrait quickly because the painter did not need to spend time elaborating forms; his task was to portray the deceased in the conventional way accepted all over the Habsburg empire in modern times. According to the convention, the rigid body of the departed, which was lying on a bier covered with a colourful carpet, was shown along the picture, with the head always situated on its right. Apart from full-figure views (Pict. 1), there were sometimes views from the waist upwards (Pict. 2) or from the knees upwards. The pictures copied not only the composition but also, to a considerable degree, the dress of the deceased so that the only individual feature of those works was the late person’s face. It was painted with great verisimilitude which was probably supposed to suggest the model’s ‘presence’ at the funeral ceremony. Postmortem changes were frequently depicted in the face, which often resulted in rather macabre effects. In this way, paintings which were to protect many viewers from looking at the dead person’s face during the funeral ceremony actually preserved the individual ‘drama of death’ for centuries to come, impressing it on viewers in hundreds of Austrian, Hungarian and Czech palace chapels and churches which served as noblemen’s mausoleums.

Similar paintings of the dead were occasionally executed in Poland but it cannot have been a common practice since merely a few have been preserved in Polish churches. Instead, since the end of the 16th century hundreds of so-called funeral portraits were painted, showing the deceased’s bust against a hexagonal metal sheet. The shape of the paintings, adapted to the head (or the rear wall) of the coffin, explains clearly how they were displayed during the funeral ceremony (Pict. 3).

The dead were depicted as living people, with open eyes and an expressive face (Pict. 4, 5). This iconographic solution probably reflected belief in the soul’s immortal life, especially as the dead were shown against a golden background reserved for saints’ images in the Middle Ages. Unlike religious paintings, however, there was hardly any idealisation in funeral portraits; they strove to give the impression of the late person’s presence by depicting their features as realistically as possible. It might seem that this convention was decidedly less dramatic than the crude portraits of corpses in the lands of the Habsburg monarchy. And yet mourners at Polish funerals not only looked the dead in the eye but could also feel they were being looked back on with unnerving perspicacity.

church of Tuczno, 1649

in Olkusz, 1682

After the funeral ceremonies were over, the portraits were unusually unfixed from the coffins to be incorporated into memorials or to be hung in churches. Looking at the pictures of living, moving people recorded in these coffin-shaped portraits, the congregation probably remembered particularly vividly inscriptions from tombstones, ‘I was what you are, you will be what I am’. They were looking at people like themselves (and not at skeletons, so different from themselves), and the peculiar shape of portraits made them realise clearly the condition of the models. On the one hand, the Polish funerary custom made it possible to hide corpses from view during the exequies; and on the other hand, it made them stay among the living, as it were, and remind them of imminent death.

Undoubtedly, not numerous but very characteristic portraits of the dead executed just after their death (Pict. 6), often encountered in the Reich and the Netherlands, performed a similar function. In these depictions, the dead body was left in peace for at least an hour after death, in the same position and with open eyes. Agony of people high up in the social hierarchy, including monarchs, princes, dukes, church hierarchs and aristocrats, was assisted also by artists who started to portray the dead just after their death, without waiting for the body to be washed, dressed and laid out. Drawings made at the time of death followed by oil paintings and sculptures made on their basis depicted, often quite realistically, the terror of agony, sufferings of antemortem illness or the first physiological changes in the body.

It is difficult to say why in the countries where showing a ‘tidy’ view of the body was avoided its more dramatic likeness was painted. Although such works were not displayed during funeral ceremonies or hung in churches and public places, even hidden in dark corners of a residence they could sometimes scare the family. All this implies that inhabitants of modern Northern Europe dreaded death and decomposition, personified in the corpse, but did not want to show that fear about their dead near and dear ones, and chose to have their likeness painted in a both ostentatious and moving way. It should be emphasised that this practice was widely accepted in modern times and did not raise any controversy. Modern art in the countries beyond the Alps, and especially in multireligious Central Europe, underwent strong confessionalisation, i.e. iconographic and formal solutions differed depending on the denomination of those who commissioned the painting. This tendency was not manifest in funeral portraits. In Hungary characteristic depictions of the dead on a bier commemorated equally Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists, while funeral portraits in the Republic of Poland showed not only the faithful of the western Church but also Uniate and Orthodox ones. Even Bohdan Chmielnicki, Cossack hetman, who rose up against the Polish rule and ‘Polish faith’, had a sizeable portrait painted for his son’s funeral.

Although postmortem portraits were painted primarily for members of the aristocracy and rich noblemen, townsmen could also have one as long as their families had both family pride and enough means at their disposal to show it off. The artistic ‘cult of the dead’ broke the class and religious boundaries, and closely united North European societies. It must be emphasised, however, that it was a deliberately sophisticated ‘cult’ which replaced the decomposing corpse of the deceased with an elegant portrait. The change resulted in all those ambiguities and paradoxes which we have observed in this brief study.

Translated from Polish by Anna Mirosławska-Olszewska

Selected bibliography:

A. Pigler, Portraying the Dead, ‘Acta Historiae Artium’, 4, 1957, nos. 1-2, pp. 1-75;

E. D. Buzási, 17th Century Catafalque Paintings in Hungary, ‘Acta Historiae Artium’, 21, 1975, nos. 1-2, pp. 87-124;

Vanitas. Portret trumienny na tle sarmackich obyczajów pogrzebowych [Vanitas. Funeral Portrait Against the Background of Funeral Customs In Sarmatia], catalogue of the exhibition in the National Museum in Poznań, ed. J. Dziubkowa, Poznań 1996;

Przeraźliwe echo trąby żałosnej do wieczności wzywającej. Śmierć w kulturze dawnej Polski od średniowiecza do końca XVIII wieku [Dreadful Echo of the Sorrowful Trumpet Calling To Eternity. Death In the Culture of Old Poland from the Middle Ages to the End of the 18th Century], catalogue of the exhibition at the Royal Castle in Warsaw, ed. P. Mrozowski, Warszawa 2001.