A systematic presentation of a social doctrine whose implementation would make humankind happy may not seem overly attractive to the average reader. Similarly, an image of a harmonious world or an optimistic vision of the civilisation at the peak of development are difficult to render in storylines. That is why, it seems, pop culture does not love utopia – it prefers to show either a politically enslaved world or a world at the edge of the final fall into barbarousness. Ravaged by nuclear wars, epidemics, demographic catastrophes and zombie attacks, the debris of human culture and totalitarian societies subjected to absolute power held by psychopathic megalomaniacs constitute the foundation for a discussion on social systems. Hence, if we hold on to the conventional distinction, popular culture has eagerly been using the anti-utopian poetics at least since the mid-20th century.

That is not to say that utopian motifs are alien to pop culture – on the contrary, it seems that especially fantasy genres owe many presentation conventions to fictitious systems. However, the utopian strand merely accompanies the plot and, unlike classical realisations in the genre which focused on a depiction of the state whose political system was particularly faultless, it now provides a purely aesthetic framework. While the classics of utopia – More, Campanella or Bacon – make sure that the reader does not miss any vital elements of their socio-political programme, to pop writers an idyllic future is usually an obvious proof of the advanced state of future humankind (the reader learns about its constituents in the course of the characters’ adventures), or a justification for the need to save a happy world from hostile interference and a pretext for the heroes’ peregrinations. Comments on the political system often act as exotic embellishments that emphasise uniqueness of the depicted reality, or reflect not so much the writer’s political programme as the socially approved principles of the desired social order. Let me illustrate the point: the political system of the Federation of Planets in Star Trek is of little consequence to the plot structure or even to the ideological message – it is only a naive representation of a golden age to come.

Yesterday’s visions of tomorrow

The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne (1874) is the final tribute to classical utopia, hidden from the world on an inaccessible island in a remote part of the globe. The micro-community that Cyrus Smith turns into a perfect civilisation, taming nature by means of his mind and technical skills, is obviously not an ancient culture based on alternative – rational – principles. It comes into being out of nothing, determined not to repeat humanity’s mistakes. The castaways from Lincoln Island are free from centuries-old limitations and can throw away the fetters of prejudice in order to create a perfect community, using marvels of modern technology, reconstructed in primitive conditions to the best of their ability. Although it is doomed to failure, it heralds the main direction of the development of the genre, which must change from utopia, a tale of a non-existent place, into uchronia, a narrative from a non-existent epoch.

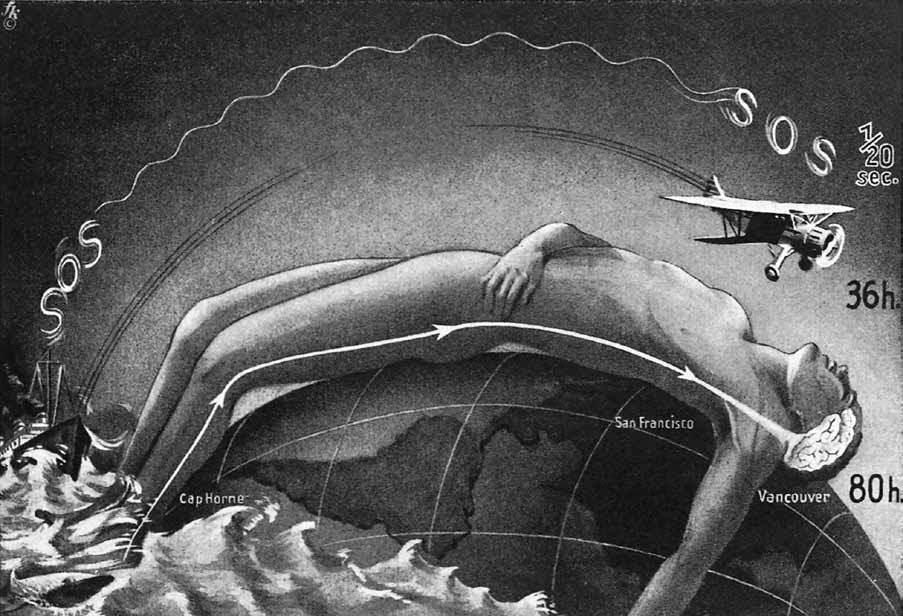

The outcome of the belief in the benefits of progress and the conviction that technology would save the world, widespread in the mid-19th century, were numerous narratives set on an Earth transformed by the human intellect. The majority, including short stories by Poe or Kipling, merely present future wonders. Yet there were also texts which focus on social and political consequences of transformations and postulate the premises on which the future idyll should be founded. They set the trend for later pop culture utopians and for the poetics of science fiction, a genre that is interested in the influence of technological transformations on the human condition. Among the novels within this convention two texts seem to be particularly noteworthy. The novel Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy (1888) is a memoir of a New Yorker who, having been asleep for over one hundred years, wakes up in the America of the future. By 2000 the world has freed itself from the 19th century ills, the new social order offers access to culture to all, and rations work according to talent. Socialist social justice and easy access to mass media (the world is covered by a pneumatic postal network) have eradicated human villainy – common aggression has turned out to be an upshot of misunderstandings and jealousy over better living conditions. Rare cases of anti-social behaviour are identified as pathologies to be taken care of by medicine rather than the penitentiary system.

A polemic text by William Morris, a British pre-Raphaelite, titled News from Nowhere (1890), shares Bellamy’s views as to the causes of human misery. Yet it radically differs from the latter as to the diagnosis: the future world, where the hero finds himself after his overly long sleep, is an agrarian utopia with no space for big cities or distribution of labour described by Bellamy. Liberated from capitalist oppression, humankind turns to nature and abandons institutional solutions. Labour, centrally controlled in Bellamy’s text, disappears completely in the reality created by Morris, in which people do what gives them pleasure. Their relationships no longer have an institutional form: everyone has the right to seek romantic love, although the principle of (temporary) monogamy is categorically upheld.

Herbert George Wells uses a similar plot device in his ambiguous utopias: a stranger from the world known to the readers is transported to an ideal community, and his observations offer an opportunity to describe and comment on rational social principles. The Time Machine (1895) is a direct polemic with Morris’s idealism. People of the future seem to be following the precepts of nature, like their forebears in Paradise, but they do so at the cost of an eternal threat from the other line of humankind – monstrous underground labourers in disused factories – and suffer intellectual decline. The rational society in the novel Men Like Gods (1923) turns out to be weak and helpless in the face of an alien aggression, while the invaders do not obey their rules, and the society itself seems morally repulsive. Again, the price for an idyll is degeneration.

Glowing adulthood

Shifting the focus of attention from new forms of social organisation to consequences of technological change coincides with conceptualisation of progress as coming of age – or of humanity reaching maturity. Its manifestation is elimination of the arduousness of the present and adoption of rationality as the principle of conduct. The metaphor , however, necessitates a transformation of the human figure (which changes like a caterpillar maturing into a butterfly) or of the vision of old age that naturally follows maturity.

The latter spirit is dominant in the texts by a generally optimistic visionary, Isaac Asimov. His short stories and novels about robots (written in the 1950s) are set in an increasingly distant future, and analyse possible repercussions of using android assistants on a daily basis. Although most of them follow a crime story formula, focusing on the issue of an at least apparent breach of the famous Laws of Robotics, which forbid an artificial creature to hurt an organic human, in the background develops a vision of a future when humanity, freed from the most onerous daily chores, can develop more and more rapidly. At the same time, the political system evolves from the national state to global governance which, through central planning and control of production and consumption of goods, eliminates social inequalities and economic backwardness.

Eventually, humans reach for the stars – in the Foundation series (which opens with the novel Foundation, 1951) humanity is depicted in the twilight of civilisation, when the scientists’ most important task is to preserve knowledge rather than develop it, so that it could become a foundation for new humanity when the old civilisation has declined.

Separation from the Earth seems a kind of cosmic rite of passage: a popular motif is that when humans reach for the stars, they will encounter other civilisations which will greet them as their own. The popular vision in Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966–1968) shows a United Federation of Planets, an association of civilisations that can travel in space and watch the evolution of potential candidates from a distance, following the principle of non-interference into underdeveloped cultures. The overstate is organised on the precept of social justice but also has liberal traits: it guarantees the possibility of social advancement within the Space Fleet to any gifted individual. The Star Trek utopia, a development of unification tendencies described by Asimov, proposes elimination of exclusion: subsequent versions of the series entrust the position of the spaceship commander to a white able-bodied American, a superannuated European, a black and a woman. This egalitarian message is the foundation for the existence of the federation which is open to interstellar races and is gradually overcoming resistance of the following ones. Acceptance of the concept of an overstate is presented as a historical necessity when subsequent races that were initially hostile to the federation become its part in the next episodes in the series.

The motif of the utopia of tolerance, expressed in the notion of an interstellar community of alien races, is surprisingly lasting, as it returns in novels, TV series and video games. In his novel The Forever War (1975), Joe Haldeman describes the process of gaining of the ability to communicate. His characters are engaged in struggle with a hostile alien race that travels to battlefields in interstellar ships which move almost at the speed of light. Owing to time dilations, they spend hundreds of terrestrial years aboard, and at the end discover that while they were travelling to the site of the conflict, both races developed so rapidly that they reached agreement. A similar vision is presented in the series Babylon 5 by Joe Michael Straczynski (1994–1998), which is set on a space station that was set up to create a common platform for communication among feuding alien races. Communication, albeit difficult, turns out to be possible, and its outcome may be evolution of a higher species and transformation of inhabitants of the Universe into energy charges, followed by a departure to an imaginary paradise of pure energy.

Beyond humanness

This concept seems to be based on a necessity to abandon humanness. Such a direction for the development of humankind is proposed by Arthur C. Clarke in his novel Childhood’s end (1953), where human maturity means liberation from the limitations and imperfection of matter. Plunged in conflict, the Earth is visited by aliens who help humans to achieve a higher level of development. Their interference is not completely disinterested, however, as they intend to hasten evolution of the human species so as to bring out people’s psychic powers, and then to reduce them to a purely mental form. Although this plan seems terrifying, its consequences are beneficial, and humankind, liberated from the limitations of matter, may experience happiness by uniting with the cosmic overmind.

The move to give up humanness and create a new culture, separate from the mistakes of the parent civilisation, may be political in nature. For instance, in Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles (1950) people exterminate native inhabitants of the red planet but it is there that they ultimately find shelter from the bureaucratic frenzy and the threat of a nuclear conflict: a desperate scholar burns a pile of papers – his memento of Earth – and names his own family ‘Martians’. The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein (1966) shows utopian traits, as well: rebel inhabitants of the Moon, mostly exiled criminals, break relations with the metropolis and defend themselves from an attempt to restore their dependence. They set up a libertarian society based on small communities with autonomous rules. It seems to be a reference to Verne’s vision, in which a small, rationally governed community is the answer to social ills.

The proposition to abandon humanness also has a biological aspect as in this case the cause of the world’s misery is not an ossified social form but corporeal imperfection. The most prominent genre here is gender utopia. Short stores and a novel by Joanna Russ (published at the beginning of the 1970s) focus on interactions between a world inhabited solely by women, reproducing via parthenogenesis, and myzoginist planets offering alleged equality of the sexes – and duly evaluate masculinity and femininity, understood essentially. In her well-known novel The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), Ursula K. Le Guin is looking for a solution in a sexually neutral society whose androgynous members gain a gender identity only in the mating season. The consequences turn out to be ambiguous: although the gender-less civilisation is gentler and does not know war, it is backward, and progress takes place very slowly – which in a science fiction novel seems to be a reproach that counterbalances the advantages of lasting peace. Another, heroic option is adopted by Suzette Haden Elgin, whose novels in the Native Tongue series (1984) are set in a dystopian America in which women have been disenfranchised, yet they put forward the idea of a feminine utopia whose foundation is the formation of Laadan, an artificial language that fulfils women’s communicative needs. In spite of the publication of a dictionary and grammar rules, the project ends in failure – a fate which utopian enterprises seem to share.

The concept of exceeding human limits, originated by single-gender utopias, has since departed from designing social systems. Trans-humanistic topology, characteristic for contemporary science fiction, focuses on the search for humanity understood individually, and not socially. This does not mean that a vision of an ideal system has been abandoned; it seems, however, that with propagation of New Age and the fantasy genre the concept of the community has gained a nostalgic tinge to it: it fosters contact with nature, rejection of technological civilisation and emulation of ancestors’ lifestyle. In this way, having lost its value of a social project, utopia transforms into idyll.

Translated by Anna Mirosławska-Olszewska